Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

The Origins of Pumpkin Beer

Pumpkin Beer Is By Far The Most Common Form Of Beer For Several Centuries And It Is All Set For Triumphant Return.

I don’t know that there’s a beer more pathologically, frequently and substantively misunderstood than pumpkin beer. I’m not talking about the perennial debate over when is “too early” for pumpkin beer to hit the taps and shelves (for my money it can’t come soon enough, so I can at least pretend the heat of summer is behind us). No, I’m talking about the general lack of light shone on the origins of pumpkin beer, how it has evolved along with the craft beer movement, and how modern pumpkin beers have evolved that paradigm yet again. Pumpkin beer has a long history, but with each era it retains the moniker while shuffling the deck on what is actually to be expected when we take our first sip, all without losing touch with its roots! Today – whether too soon or not – we’re going to take a walk through the pumpkin patch and down memory lane to discuss where pumpkin beer came from, how it got here and where it’s going.

The Colonial Era

As American as apple pie,” the saying goes, but it could just as easily have been “as American as pumpkin pie.” To your average colonist in North America in the 17th and 18th centuries, pumpkin products of all kinds – pies, mashes, beers, breads, you name it – were ubiquitous. Why? Because there was a veritable unending supply of the things. Have you ever seen an “accidental” pumpkin patch? I have. My wife’s parents thought it’d be good ground cover for some lawn in their side yard – and I spent many an unpleasant hour helping tame the thing. Pumpkins grow like weeds, wandering and weaving and wending, and it’s no wonder that in an otherwise resource-strapped place like Colonial America that pumpkins found their way into everything. As one popular saying went, “we have pumpkin at morning and pumpkin at noon. If it was not for pumpkin we should be undone!”

This included, from the earliest days of the colonies, pumpkin beer. The “pompion” was derived from the mashed and fermented pulp of pumpkin, and probably not much else. Colonists had limited access to wheat and barley, and those were generally used for bread flour, with oats and other cereal grains used in cooking and for livestock feed. But pumpkins they had in abundance, and while contemporary recipes are scarce there are frequent mentions of pumpkin and other adjunct ales in the writings and records of the time. Pumpkins were not used for their flavor: they were simply a source of starch, converted into fermentable sugars, just as with malted barley and other adjuncts. Apples, pears, squash, corn and other “local” agricultural products were also used as a source of fermentable sugars, but pumpkin stood out in terms of its availability and its ability to produce (with some age) a fairly clean finished beer. While it would not have been unheard of to add spices and hops to pumpkin beer, there do not appear to have been any “go to” flavoring additions. You might say that this was a rustic, “farmhouse” product! Spruce, ginger, molasses, even ground ivy were added to the ad hoc recipes brewed by the colonists.

The popularity of pumpkin beer faded through the decades, however. No specific explanation is offered for this shift, but the most likely explanation is the simplest one: as agriculture developed in the new United States and cereal grains became more readily available, the necessity of using pumpkins as starchy source material fell away. We can also assume that waves of emigrating British, German and Czech brewers – accustomed to working with traditional brewing grains – would have had no particular reason to make use of the unfamiliar New World pumpkin. Whatever the reason, pumpkin beer all but disappeared from the American brewing landscape until the 1980s.

The Rebirth of Pumpkin Beer

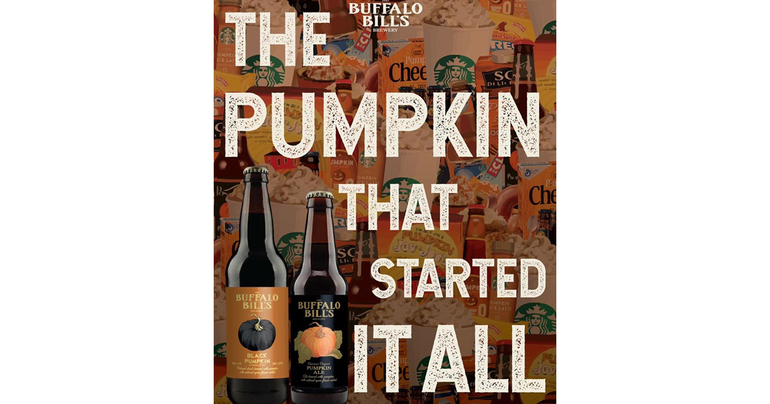

Necessity may be the mother of invention, but curious brewers are probably its quirky aunt; it is thanks to one such brewer that pumpkin beer reentered the national drinking scene. In 1985, Bill Owens was brewing and selling beer at one of the first outposts of the craft beer movement: Buffalo Bill’s Brewery in Hayward, CA. Owens had run across a recipe for pumpkin beer in the writings of George Washington, in which Washington described the brewing operation at Mount Vernon. Intrigued, he jumped in with both feet, ordering seeds and literally growing the pumpkins used in the early test batches. Roasted and then mashed in with a version of Bill’s Amber Ale, the pumpkin added… nothing of consequence.

It’s at this moment that expectation meets up with perception and leads to innovation: when we think of “pumpkin flavor,” we are actually not thinking of the flavor of pumpkin. We’re thinking of the flavor of pumpkin pie, which is driven not by pumpkin (largely flavorless) but by cinnamon, clove and other spices. Bill and other brewers quickly focused more on the spice blend used in pumpkin beers, and many (most?) abandoned altogether the use of pumpkins in their pumpkin beers. With a rich malt backbone and restrained hop character supplemented by spice additions, “pumpkin beer” began to define itself as a distinct fall seasonal style – even without the pumpkins. Today, the Brewers Association style guidelines differentiate between “Pumpkin/Squash Beer,” which is brewed with pumpkin and without spicing, and “Pumpkin Spice Beer,” which may or may not contain pumpkin but does use spices to create an evocative flavor profile. The Beer Judge Certification Program guidelines lay out the rough parameters of an “Autumn Seasonal Beer,” which captures both. For professionals and homebrewers, pumpkin beer is as well-known as it is derided for pushing its way onto shelves and taps too early in the year.

Pumpkin Beers Today, Yesterday and of Yore

Brewers and drinkers alike get bored easily, so although there are still any number of mid-strength amber ales with pumpkin pie spices on the market, they’re hardly alone: new and exotic variations on the pumpkin beer are now seasonal favorites. The “original” Buffalo Bill’s Pumpkin Ale is still brewed and sold, and it’s joined by nationally distributed versions in the same vein (Dogfish Head’s Punkin Ale comes to mind). But pumpkin beers have evolved far beyond their late-20th century cousins.

Today, we see strong and barrel-aged versions of the pumpkin ale in beers like Avery’s PumpKYn and Rumpkin (bourbon and rum barrel-aged, respectively), and Good Gourd Imperial from Cigar City. Then we have any number of roasted and rich varieties like Buffalo Bill’s own Black Pumpkin, Pumpkinator from St. Arnold’s (not, as its name would suggest, a pumpkin Doppelbock, but the idea has merit), and Southern Tier’s Warlock – each of which shifts the base style from an amber ale to a strong stout, sometimes with cocoa or coffee added. And then you find lighter and brighter riffs on the pumpkin, like Sam Adams’ Pumpkin Batch Saison and Almanac’s Pumpkin Sour. Truly, it seems like every brewery has some take on the venerable pumpkin ale.

For a beer that is the subject of a postmodern, too-hip campaign to trash it every September (OK, every August), there are certainly a lot of pumpkin beers about! What is remarkable, though, isn’t that we see so many of these beers on the shelves – it’s that we can clearly see the connection between the rustic (or at least rustic-seeming) pumpkin beers of today and their forebears in the 17th and 18th centuries. Brewers in the 21st century not only appreciate and recognize the “brew with what you’ve got handy” ethos, they embrace it heartily. Pumpkin beer is, quietly, an exemplar of exactly what we want to see in craft beer: use of local and sustainable ingredients, creative recipe design, and a product that is both flavorful and fuels our nostalgia and whimsy.

Not bad for a humble pumpkin.