Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Are There Too Many Craft Breweries?

If someone asked you "are there too many craft breweries in America," what would you say? Do you agree/disagree/don’t know?

I would probably ask, “Too many breweries for what?”

Too many breweries for any mortal to experience in a lifetime? Possibly. You could do it if you owned your own jet and had a stomach similar to Andre the Giant’s.

Too many breweries to be sustained economically in the long run? Absolutely not. Craft beer is often a job-creating, friendship-generating beacon of positivity.

Too many breweries for the good of all breweries? This is a definite yes.

Before I’m chased out of town with malting shovels and electrified hydrometers, I’d like to clarify that too many breweries isn’t a problem for the consumer, of course, nor is it one for all brewers. It’s just a fact that must be taken into consideration for those associated with the industry. Let’s look at the numbers.

By the Numbers

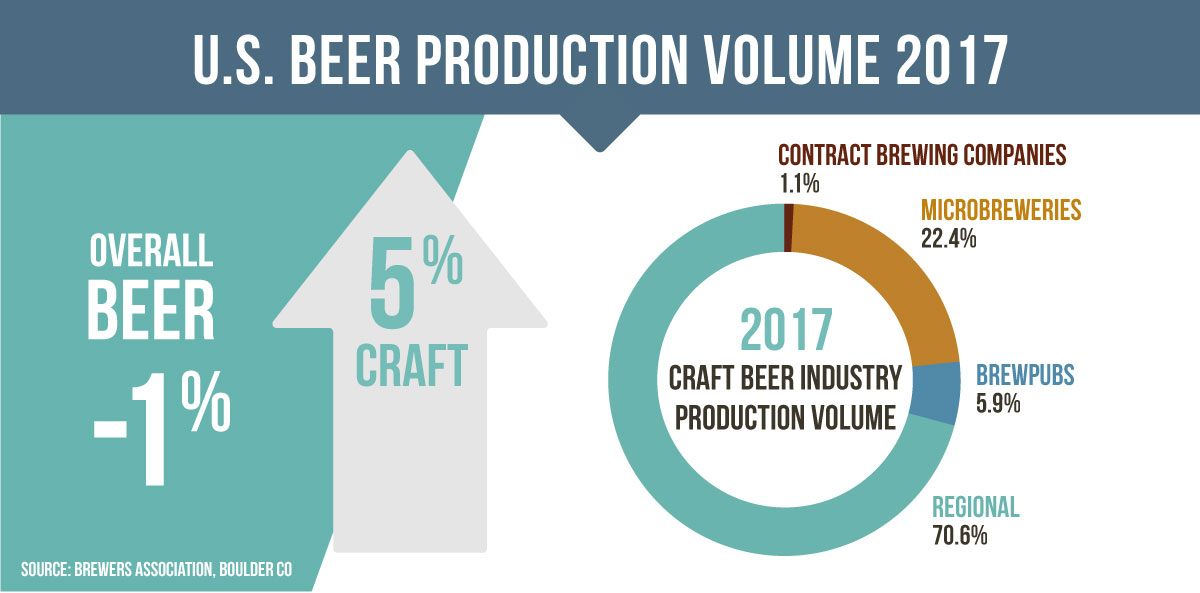

The Brewers Association estimates nearly 1,000 new breweries opened in 2017, for a total of 6,372 U.S. breweries. Out of those 6,300-plus craft breweries, more than 4,200 have opened in the past five years … and there are around 2,500 in the planning phase.

What that tells us right off the bat is that a very competitive marketplace is about to get far more competitive, simply from a numerical standpoint. There’s more beer occupying the same amount of space.

If you’re a brewery in planning, you’ve got to have a very solid plan, because this is the proverbial “bubble bursting” that is so often spoken of in hushed, fearful tones. However, doomsday imagery doesn’t really apply.

Fierce competition is starting to force out the weaker competitors, but at this stage, it’s not going to cause a catastrophic meltdown. This is now a proven industry with infrastructure it didn’t possess the last time a shake-out scenario took place in 1997. We’ve got college degrees for brewing, lobbying and legislation in place, and multiple layers of craft retail and tourism, among others.

Point being, craft is now a generational entity. The same could be said for the internet after the Dot-Com boom and bust. Good beer is here to stay, and now it’s just a matter of how things play out.

Using BA-defined terms, craft’s broad segments are regional breweries (defined as any craft brewer making between 15,000 and 6 million barrels annually), microbreweries (under 15,000 bbls) and brewpubs (more than 75 percent of beer sold on-site). Of these segments, about 200 are regional, 3,800 are microbrewers, and 2,250 are brewpubs.

The number of breweries that closed in 2016 was 97. Last year that number grew to 165, an increase of 70 percent. Brewpubs accounted for 64 closures last year, while microbreweries accounted for all 101 of the other closures; regional brewers saw no closures.

Craft brewers that have been able to squeeze into large outlets and sell en-masse (New Holland, Bell’s, New Belgium) will maintain their foothold just as surely as AB InBev’s craft acquisitions, like 10-Barrel and Goose Island.

An Epic Battle

Breweries that can establish themselves at a regional level are generally going to be more stable than micros and brewpubs, which are left to fight a bitter battle in the trenches. Realistic success in these small brewing categories must be met with realistic expectations. Exponential growth is generally not going to happen, and a following must be carved out one foot at a time without the boost of retail shelf space.

The battle for shelf space is being waged on multiple fronts with uneven playing grounds; both a civil war and one among nations.

Keep in mind that craft is being fought and bought by larger powers. Call it what you like – David and Goliath, craft and macro, local vs. low-cal – but these entities are wielding vast dollar amounts to sway the consumer away from local beer through a variety of tactics. Marketing is an obvious one, but perhaps the most potent tool at big beer’s disposal is its appropriation of the craft identity.

These macro-operated craft brands are designed to drive down perceived value, reclaim precious retail shelf space and clog distribution channels, severely inhibiting the growth of local craft brands. What we get is thousands of breweries fighting for just a handful of spots.

Supposing a microbrewery did find its way into a grocery or chain outlet, it would still face an upward battle against its more established regional brethren. Smaller operations have a harder time maintaining consistent production in both quality and quantity – one misstep in the eyes of a retailer and you've lost your chance.

Since regional brewers are better positioned to maintain quality and sell to retailers at lower costs, there isn't much incentive for large retailers to buy from microbrewers. Those craft brewers that have been able to squeeze into large outlets and sell en-masse (New Holland, Bell’s, New Belgium) will maintain their foothold just as surely as AB InBev’s craft acquisitions, like 10 Barrel and Goose Island.

This is important, because with retail locked down, more than 6,000 microbreweries and brewpubs are vying for keg and tap sales on a hyper-local level. But there simply aren’t enough taps for all these breweries, and in a hypothetical scenario where there were enough taps for every SKU from every brewery and they were all being enjoyed equally, the turnover rate for a keg would be too low to sustain production.

Why Breweries Fail

We run into another briny pickle when we consider the “49’er” climate into which the majority of these breweries matriculated. Growth was exponential, almost a sure thing for investors, and the American Dream seemed so attainable that many who might not have been prepared to open a brewery did so anyway.

Perhaps they didn’t account for the inevitable hop shortage, rat infestation or contaminated batch, or they just assumed craft would continue skyrocketing, but if one too many things went wrong they were toast – a survival of the fittest scenario.

Breweries that have folded likely fall into one of the following categories, if not all:

An undercapitalized entity that decided to bootstrap through friends, family and second mortgages. It has been said that whatever money you think you need to start a brewery, you should double or triple it. Landlord and rent issues have been cited as a common bugaboo for the small brewer; increases in rent or difficulties in finding a suitable, convenient location to run their business have scuttled many of these companies.

Maybe the financial capital is there, but the experiential capital is not. Junior made some rookie mistakes after papa put him in charge, like scaling immediately or simply going in with the wrong idea of what it meant to run a brewery.

Perhaps the money and experience is there, but the beer isn’t cutting it. These days, the beer doesn’t even have to be bad for a business to fail. As a friend said, “everything’s either the same, or too out there.”

Takeaways

So, what can we learn from all of this? The regional players and macro brewers are going to absorb a lot of craft’s growth over the next few years. Small brewers should plan on staying relatively small, and building loyal local followings with limited, proven SKUs. They must have a very clear plan and identity and stick to it, with a steady focus on being the best at whatever they choose. If a brewery doesn’t stand out, it’s not going to survive.

How can a brewery in planning stand out these days? Start with a focus on consistency in product and identity, and you’ll carve yourself a nice niche. Just don’t bite off more than you can chew.

If you’re making IPAs, they truly have to be the best out of thousands and marketed equally as well. Good taste, good name, good can art. If you’re getting experimental, it better be palatable for the majority until you can afford to brew liquid horse blanket and take the hit.

Another avenue could see a brewery focusing on one style only, perhaps even a lesser-known one. This checks multiple boxes, helping build a brand that stands out and keeping the brewery from spreading itself too thin.

Lastly, here’s a burgeoning avenue that might be worth considering – exported beer from the U.S. is growing considerably. The world has taken note of American craft, and breweries that have built a following with quality beer might do well to explore sending some abroad; or as some might say – outside of the bubble.

Comments