Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

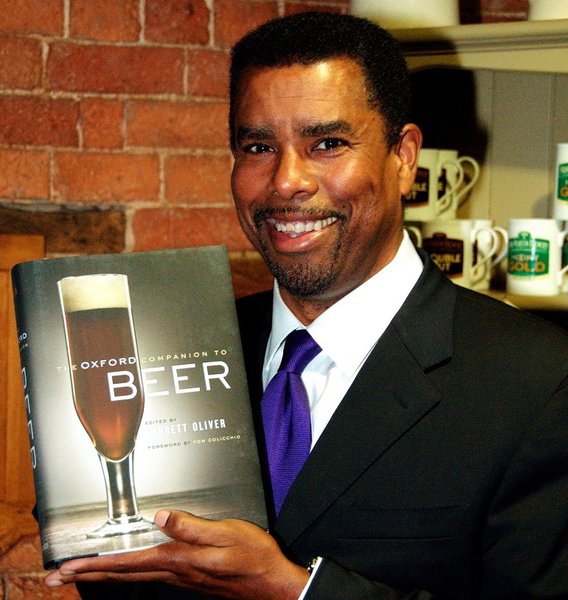

Garrett Oliver of Brooklyn Brewery

Garrett Oliver, the founder and brewmaster of Brooklyn Brewery is one of the most important figures in craft beer. As Brooklyn's website entails, Oliver is known for "his elegant lectures on the history of beer and the art of brewing, his extensive knowledge of movies and literature and his two hats. He is editor-in-chief of The Oxford Companion to Beer, author of The Brewmaster’s Table and winner of the 2014 James Beard Award for Excellent Wine, Beer or Spirits Professional. He’s a world traveler, snazzy dancer and we’re starting to suspect he doesn’t sleep."

Brooklyn’s Bridge to Brewing Glory

Late last year, following a two-week stay in Japan that included collaborating with one of the Far East’s elite breweries, Kiuchi, the makers of Hitachino Nest, there was one more stop before Garrett Oliver, the globetrotting author, instructor and Brooklyn Brewery brewmaster, headed back to his New York home. Joining forces with the celebrity chef Tom Colicchio at his upscale Craft Atlanta restaurant, Oliver helped set the stage for one of the most extravagant beer dinners the South has ever hosted.

To match five courses of Colicchio’s culinary mastery, Oliver uncorked bottles of Brooklyn’s Local 1 and 2, the pale and dark Belgian-inspired strong ales; Wild 1, an unreleased batch of barrel-aged Local 1 re-fermented with “wild” yeast direct from his private stash; and Black Ops, an imperial stout aged for four months in Woodford Reserve bourbon barrels and finished with Champagne yeast.

But perhaps the most noteworthy beer on hand was Oliver’s most eccentric amalgam of gastronomic harmony to date, the Brooklyn Reinschweinsgebot, a brown ale also aged in bourbon barrels that was later taken through a “fat washing” process using rendered bacon fat from Benton’s Country Smokehouse in Tennessee. It was paired with Colicchio’s stout-braised pork cheek with sauerkraut, quark cheese ravioli and cracklin’ gremolata, making for the most intriguing course of the evening.

These days, saying that ales and lagers have equaled or even surpassed the prestige of wines, which once monopolized white-clothed tables, is no longer far-fetched, and Oliver, 47, remains a pioneer of the phenomenon.

“Slowly but surely, I kind of fell in love with making beer and that became a passion which tied itself into the interest I already had in food. By 1988, I would say that I had a pretty good idea that it might end up being beer instead of film that I would end up doing,” Oliver said.

“The thing that I really want people to realize is the range of flavor in beer is factually much wider than the range of flavor in wine,” he said, while sitting next to a roaring fire in a Midtown Atlanta hotel lobby decked out in a crisp navy blue blazer emblazoned with a Brooklyn Brewery crest. “Put it this way – and I don’t mean this to sound ignorant because I love wine and have sat on panels with The New York Times talking about it for hours – but wine generally tastes like wine. And it tastes like wine in a lot of different ways, but when I make a beer that tastes like chocolate, cherries, smoke or caramelization, I can cover a range so much wider than you are ever going to see in the wine world. When I do wine versus beer against a sommelier with food, my rack of weapons is always so much broader than the other guy’s. I’ve got kung-fu they will never see coming, so that makes me hard to beat!”

This is Garrett Oliver, the eminent beer expert and dedicated gastronome who is on a global mission to spread the love for these two pleasures of life. His success is now undeniable, and the road he traveled to get there has been quite remarkable.

Most venerated culinary epicures and beer experts have developed their expertise by attending prestigious culinary and brewing schools, but Oliver’s path was more of a less-traveled detour. Reflecting back on his upbringing in Queens, New York, he remembered that exotic cuisine was often served at the dinner table. “We were always people who were into food,” Oliver said. “I grew up in Queens, but by the time I was 13 we owned a horse Upstate, and we used to go and hunt pheasant, quail and partridge on horseback with dogs and guns. We were weirdoes, yes, but we were serious.”

Garrett Meets Beer

While he developed a refined palate as a teen, Oliver’s first experience with beer was not as sophisticated as his early food ones were. “My first beer was when I was 12, and my uncle Bill served it to me down in South Carolina I think. I kept bothering him, asking, ‘Uncle Bill, let me taste your beer.’ I think it was Miller High Life out of a can, and finally he says, ‘Fine, here it is.’ I was like, ‘Blah!’ and spit it out. I didn’t touch any beer again until I was about 16, when I started drinking Guinness.”

He went on to attend Boston University, where he majored in broadcasting and film. Oliver aspired to be a video director but was not able to find any promising opportunities post-graduation. Luckily, he had a conversation that would eventually change his life forever.

“My best friend was moving to England, and he said that I could get a work permit for a year under this program and asked if I wanted to go,” Oliver said. “I didn’t have any particular job prospects. I loved a lot of the music that was coming out there at the time. I never lived in another country, and I wanted to go see something new. That was in 1983. I was 21 when I graduated, so I was like, ‘Let me get out there and see some stuff.’”

After balancing his temporary job with train-hopping to countries like Belgium, Germany and Hungary for a year, Oliver returned to the United States. His invaluable experiences in Europe had enhanced his appreciation for the finer things in life, including traveling, fashion, culture, food and – yes – beer. Unfortunately, anything even remotely close to a Belgian blonde or a helles bock was nonexistent back home. “It was when I moved to England when I fell in love with beer,” Oliver said. “I had all of these different beers, and then when I got back I was like, ‘Damn. What’s this stuff? I can’t drink this!’” It wasn’t long before Oliver purchased a homebrewing kit.

“The first beer I made at home was actually called ‘Blast’ – I named it after a very obscure literary reference to a writer in England named Wyndham Lewis, and he had a journal called BLAST, where he would ‘blast’ some things and ‘bless’ other things that he thought were great things in life. It was a pale ale, kind of like a mild Samuel Smith Pale Ale, but it was not the best thing you ever wanted to have,” Oliver recalled with a laugh. “It kind of tasted like apple cider."

“Slowly but surely, I kind of fell in love with making beer and that became a passion which tied itself into the interest I already had in food. By 1988, I would say that I had a pretty good idea that it might end up being beer instead of film that I would end up doing.”

There was one problem, however. Upon returning home from England, Oliver landed a temp position at a law office in New York City that turned into “a pretty cushy job,” he said. “I got paid a lot of money, I had a window office on the 52nd floor of what was then the Pan Am building. Park Avenue was out in front of my window like a runway. I liked my boss and the work wasn’t boring, so it was a better job than most people were going to have.”

"Moving to England is when I fell in love with beer," Oliver said. "I had all of these different beers, and then when I got back I was like, 'Damn. What’s this stuff? I can’t drink this!'"

But one summer afternoon in 1989, Oliver heard of an opening for an apprentice at the Manhattan Brewing Company, the pioneer of the brewpub concept in New York City. Manhattan Brewing promoted an authentic pub experience complete with wooden pub tables and traditional copper kettles that it used to produce award-winning brews, like Manhattan Amber and Manhattan Gold Lager. Realizing how much he was enjoying the challenge of brewing beers similar to the ales and lagers he indulged in while overseas, Oliver saw Manhattan as the ideal arena to perfect and broaden his craft. He went for it and managed to land the position.

After experiencing the strenuous and hazardous days on the job with Manhattan, though, Oliver questioned his new career move. “For the first month I was saying to myself, ‘What the hell have I done?’ I am making one-third of the pay, and I burned off several square inches of skin off of one arm from a splash of hot wort. But after about a month or so, I kind of felt the rhythm of the whole thing and never looked back.”

While Oliver persevered and developed his brewing skills, a blossoming venture based in an adjacent New York borough was also on a mission to break up the mega-brewers’ monopoly on taps and coolers citywide – and eventually beyond.

Brooklyn Brewery Is Born

Steve Hindy had spent six years learning how to brew beer while serving as a correspondent with The Associated Press in the Middle East during the late 70’s and early 80’s. Making a brownstone in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood his home upon returning to the States in 1984, Hindy, like Oliver, was inspired by his world travels and wanted to make a career change to help shake up the monotony of mass-produced, watered-down lagers. Perhaps Brooklyn’s brewing history further fueled his thirst for quality beer.

The German immigrants who demonstrated their allegiance to the Reinheitsgebot, the centuries-old purity law, ran approximately 50 breweries throughout Brooklyn during the 19th century. Unfortunately, the implementation of Prohibition from 1920 through 1933 was followed by the reign of the Midwest’s heavily marketed and widely distributed pilsners brewed with cheap ingredients like corn and rice. By 1976, the last remaining Brooklyn brewing families, Schaefer and Liebmann (the maker of Rheingold), could no longer prosper and closed their doors for good.

In Hindy’s eyes, the time had come to revisit the rich brewing tradition of his beloved borough. By fate, a neighbor named Tom Potter shared the same sentiments strongly enough to quit his job as a lending officer with Chemical Bank. With a mutual fondness for their environs, the enterprising duo founded the Brooklyn Brewery in 1987. The eye-catching logo – a white, serif-happy “B” sandwiched between two yellow dots that was designed by the artist famous for the “I Love NY” logo, Milton Glaser – along with Brooklyn Brewery’s slogan, “the Pre-Prohibition Beer,” completed the identity of their flagship brew: the robust, amber-hued Brooklyn Lager.

After hand-labeling their first batch for public consumption, Hindy and Potter were confronted by two major obstacles – skepticism that Brooklyn’s Lager would sell since it cost as much as some “pricey” imports and unyielding distributors who were not willing to carry a brand that was virtually unknown. The duo countered by purchasing a small delivery truck that they branded with their logo and drove around selling their Lager, and they cut costs by contract brewing out of a Utica, N.Y., plant. Gradually, their brewing venture began to grow.

Enter Oliver

The Brooklyn Brewery founders, joined by partners Jim Munson, Mike Vitale and Ed Ravn, made slow yet substantial progress that eventually led to the brand’s expansion. To bring some of the brewing closer to home, they acquired a former matzo ball factory in the Williamsburg section of northern Brooklyn. Then Hindy, Potter and their associates received word of a burgeoning brewmaster who was garnering a reputation for creating exciting ales and lagers with Manhattan Brewing. Oliver, it seemed, would be the perfect fit to not only oversee the Utica operation but to also design the future Williamsburg headquarters. In hopes of making New York a beer capital once again, he joined the Brooklyn team in 1994.

“For the first month I was saying to myself, ‘What the hell have I done?’” Oliver remembered. “But after a month or so, I kind of felt the rhythm of the whole thing and never looked back.”

On May 28, 1996, the Brooklyn Brewery and then New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani held a ribbon-cutting ceremony that officially opened the new Williamsburg brewhouse. Giuliani happily toasted the site’s inaugural brew, a glass of Oliver’s interpretation of a Bavarian-style wheat beer called Brooklyner Weisse. From this moment on, the brewing world began praising virtually everything Oliver conceived, from the East India Pale Ale to the Black Chocolate Stout to Brooklyn’s Pennant Ale ’55, and – for those fortunate enough to get their hands on some – creative specialty beers like the Reinschweinsgebot.

The Brewing Icon

The Brewing Icon

While Oliver’s well-regarded roster of ales and lagers blossomed, so did his thirst to share his passion with the world. He has become one of the most in-demand authorities on beer and has been tapped to judge numerous prestigious beer competitions like the Great American Beer Festival; give lectures internationally; host hundreds of beer dinners; teach cooking courses at institutions like the French Culinary Institute; make guest appearances on TV and radio networks including CNN, NPR and Bravo; and write books that continue to enlighten aspiring epicures and beer lovers worldwide.

Oliver co-wrote his first published work, “The Good Beer Book,” with Timothy Harper in 1997. Then, in May of 2003, he released “The Brewmaster’s Table: Discovering the Pleasures of Real Beer with Real Food,” which reaped much acclaim, including the International Association of Culinary Professionals (I.A.C.P.) Book Award the following year. His next literary work will be an encyclopedia of sorts that’s set to be released in 2011 and will be called “The Oxford Companion to Beer.” Oliver called the work “a monster” that further delves into the art of pairing beer and food.

Amazingly, while wearing all of these hats (though only one of which has its own Twitter), Oliver still manages to find time to collaborate with some of the world’s finest brewers, including the brewmaster Hans-Peter Drexler of Germany’s Schneider brewery. Their partnership resulted in the Brooklyner-Schneider Hopfen-Weisse, a fantastic dry-hopped weissbock that honored the brewing excellence of the Bavarian Hallertauer hop region. Exciting beer connoisseurs throughout the world, future alliances with breweries including the aforementioned Kiuchi are also in the works.

The night of the Craft Atlanta beer dinner, Oliver admitted that he was looking forward to finally returning home to New York. But first, it was once again time to answer his life’s calling: to profess the history, variation, complexity, creativity and countless other blissful qualities beer encompasses. Undoubtedly, the decision Oliver made back in 1989 to leave that “cushy” law job on Park Avenue has paid off. He is now living the dream as a true beer authority.