Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

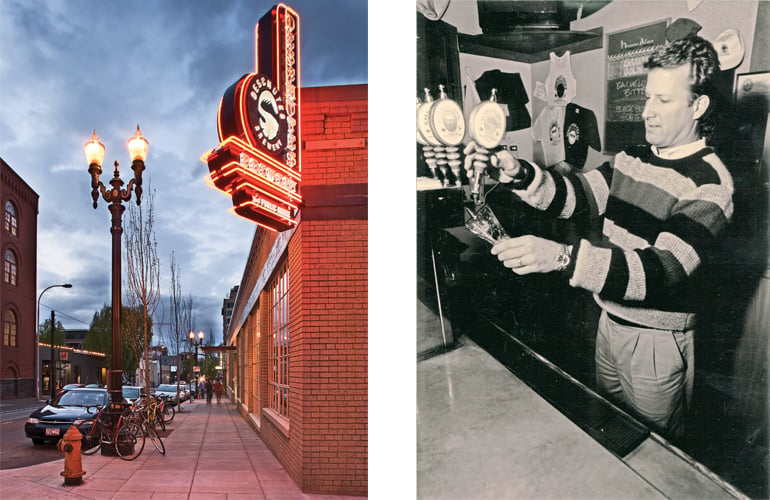

Gary Fish of Deschutes Brewery

Gary Fish is not one of those pioneer Oregon brewers who wore a welder’s mask as easily as brewer’s rubber boots and built his own brewery like the Widmer brothers.

Instead, Fish was a self-proclaimed restaurant guy when he started Deschutes Brewery as a brewpub in Bend, Oregon in 1988 at the age of 31. And he remains a restaurant guy at 57, albeit one with a lot more experience and a few scars incurred from guiding a small brewpub in a depressed lumber town to become Oregon’s largest brewer and the sixth largest craft brewer in the country. Deschutes Brewery sold 713 barrels of beer in its first year – a volume that far exceeded his idea of selling a few barrels of excess capacity to a couple of nearby Central Oregon resorts – and sold more than 285,000 barrels of beer last year in 26 states.

As one of Oregon’s leading businessmen, Fish has won a lot of honors over the years. He’s a founder, past president and current board member of the Oregon Brewers Guild, and is now chairman of the board of the Brewers Association, the national craft brewing trade group. Fish is active in Bend business groups, was past president of Rotary and the Chamber of Commerce, and has several civic and trade awards on his mantel, including Ernst & Young’s Pacific Northwest Entrepreneur of the Year for 2013. And like employee-owned Full Sail Brewing, which opened the same year in Hood River, Deschutes is perennially named one of the best workplaces in the state.

“Pubs,” says Fish, “are where we go to reclaim our humanity.”

But despite the accolades, Fish remains a restaurant guy at heart. “I’m an old school manager,” said Fish in a recent interview at the Deschutes Portland pub in the Pearl District, a beautiful, woody space that embodies his ideas about local art, brewing, food and the ideal pub experience. “I’m the first one here in the morning and the last to leave at night. I may not be the smartest guy in the room, but I can work as hard as any.”

Fish neglects to mention some of his other attributes in that brief evaluation: loyalty to his people, a genuine feel for the market and abiding respect for his customers and for the beer. But hard work has certainly been a big part of the Deschutes success, and remains so. “It’s interesting to look at the numbers,” he said of the brewery’s national ranking, “but then you toss the score card away and get back to work.”

The score card shows that Deschutes is on target to brew 320,000 to 340,000 barrels this year. “We’re growing at a comfortable pace, but we may ratchet back a bit,” he said. “We’ll open Michigan later this year and that’s it for a while, except for the Zarabanda Saison we’re making for Jose Andreas’ restaurant in Washington D.C.”

Current capacity for Deschutes, located alongside the Deschutes River, is about 420,000 barrels a year. They’ve been brewing around the clock six days a week during the summer and are looking to staff the brewery 24/7. They’re expanding the packaging line and will soon add cellaring capacity. “Then we need to add to the existing brewery or add another brewhouse,” Fish said. “Things will ease, but you never get rid of the pressure, you just shift it around.”

What may help ease the pressure is building a second Deschutes brewery closer to East Coast customers. “I’ve been pretty open about the fact that we need another brewery,” said Fish. “As we continue to expand eastward, it no longer makes sense to brew beer in Bend and truck it across the country.”

Growing physical capacity is just part of the equation, however: Fish is well aware that in the volatile craft beer market, being big is not an unmixed blessing. “The consumer is in full-out exploration mode, and brand loyalty in the classic sense is not an issue,” he said. “The consumer is interested in pursuing new experiences and we need to keep building on the artistic side of brewing, on blending barrel-aged beers, on sour beers, on constructing flavors.”

Bend was a depressed lumber town of about 12,000 people and one sawmill when the Deschutes Brewing Public House first opened — well before the brewery was built on the river. The Portland pub gave Deschutes a total of 40 taps.

There’s no better example than the glasses of Cultivateur saison that we sampled at the pub. It’s the latest in the Deschutes Pub Reserve Series: a beautiful, tart saison, redolent of peaches, apricots and spices; notes produced during fermentation, not from additions of fruit, because Cultivateur is a prime example of Deschutes’ painstaking approach to brewing.

It’s a blend of four batches of three beers brewed at the Bend and Portland pubs and aged for as long as 13 months in oak pinot barrels with brettanomyces and lactobacillus. For a big brewery to expend that kind of time and effort aging and blending a beer is impressive, but Cultivateur is just one of 20 barrel-aged beers that Deschutes Brewery will release this year.

They range in scope and frequency from the annual and eagerly awaited release of the Abyss and the Dissident, to series such as the Pub Reserve beers. Even more esoteric are the one-time only beers such as Conflux Collage, an aptly named interweaving of two Deschutes barrel-aged beers blended with two beers from Portland’s Hair of The Dog Brewing Company – Fred and Adam.

“We currently have about 3,000 working casks,” says assistant brewmaster Ryan Schmiege, “and about 15,000 square feet devoted to the barrel aging program.”

That’s what Gary Fish means when he talks about constructing flavors and why he defers to his staff of 30 or so brewers: “I can brew, I’ve been to brewing school,” he said, “but brewing is not the best use of my time because I’m not like our brewers – those guys can really make the equipment sing.”

He has strong feelings about where such sublime beers should be enjoyed, too: “Beers like this should be shared among friends,” Fish said. “I cringe when someone posts that they’re drinking a bottle of The Abyss by themselves. Our core value is to build a healthier society and the pubs are a big part of that because they’re a place to socialize, to talk face-to-face – people don’t do that anymore except in a pub: young people, old people, white collar or blue – they’re all talking with one another. That scene doesn’t play out in a wine bar or a cocktail bar. The pub is a unique institution, it’s where we go to reclaim our humanity.”

They’re also a valuable tool for Deschutes and its brewers: “Between the Portland pub and Bend we have 40 different taps,” he said. “We convene two very large focus groups every day at 11 a.m.”

Both Deschutes pubs are consecrated to good beer as a basis for human interaction, and each reflects the company’s support of local artists – the wrought iron hop vines in the Bend pub and the massive reclaimed timbers with their chainsawn sculptures of Northwest wildlife that decorate the Portland pub.

Neither Oregon nor Bend were on the list when Fish looked to start a brewpub in the 1980s. He grew up in Northern California, the son of a contract grower for big wineries such as Mondavi and Korbel. At age 16 he was a dishwasher at a winery-themed restaurant in Orinda, California: “Long enough ago that when you ordered a carafe of white wine, it was Gallo jug wine,” he said.

“Beer was the same thing.” he said, “American lagers were ubiquitous whether they came from national or regional brewers.” But the son of his dad’s business partner was developing a brewpub and the numbers made sense to him. Instead of the five to six year payback of a wine operation, a restaurant that brewed beer could get paid in cash within 30 days of buying the ingredients. “Once I realized that, the lights just started going off.”

In 1987, he sold his share in the Salt Lake City restaurant he was managing and started working with Ed Brown, who was setting up Rubicon Brewing in Sacramento. Meanwhile, he and his wife scoured Northern California for a location for their brewpub, but had no luck. Then his Oregon-born parents attended a college reunion in Corvallis and visited Sun River near Bend and fell in love with it – they couldn’t stop talking about how cool the area was.

“When I visited town and floated the idea of opening a brewpub, I talked to city officials, local businesspeople, the Oregon Liquor Control Commission and everybody said, ‘I’ll be your first customer.’ Everybody but the banks were with us.”

Mid-1980s Bend was nothing like the vibrant, bikey, outdoor sports-loving hub of Central Oregon that it is today, with 80,000 people and 20 craft breweries. It was a depressed former lumber town of about 12,000 people with one sawmill, a lingering cloud of economic gloom and – most emphatically – no breweries.

A cornerstone of Oregon craft, Deschutes is expected to brew as many as 340,000 barrels in 2014. “It’s interesting to look at the numbers,” said Fish, “but then you toss the score card away and get back to work.” More than 25 years after first opening in Bend, Fish is now serving the children of some of his first customers.

“We didn’t know what we didn’t know,” said Fish, a phrase he uses often to describe the pitch of the Deschutes learning curve. “I brought my wife to Bend for our anniversary in 1987 and we moved to town around Thanksgiving and we opened the pub in June of 1988 in a former law office on Bond Street downtown.”

The Bend brewpub was the tenth restaurant opening of his career so he was ready for a flood of applicants for servers and kitchen crew. “I opened the door that Monday morning at 8 a.m. to the sound of crickets: there was nobody there,” he said. “By the end of the week about 15 people showed up, mainly because they’d been fired from every other place in town, and I had to hire a dozen of them... It was quite a crew. I don’t know if I can laugh about it now – crack a smile, maybe.”

“Bend was a very blue collar town at the time, and I sometimes thought people came by the pub only to see us fail, but we survived because we made good beer.” That’s because Fish didn’t depend on local talent to staff the brewery. He brought in Canadian brewery consultant Frank Appleton, who set up the brewhouse and originated the recipes for the first three beers: Cascade Golden Ale, Bachelor Bitter and Black Butte Porter (which remains one of the best selling bottled craft beers in the country).

He hired John Harris as his first brewmaster. Harris had brewed a couple of years for the pioneering McMenamin brewpubs and was an inspired choice: he tweaked the recipes – making Black Butte Porter more roasty, for instance – developed new beers such as Jubelale and the flagship Mirror Pond Pale Ale, and shepherded the brewhouse through a rough patch of infected beer caused by installation problems. He has since gone on to a couple of decades at Full Sail and recently opened Ecliptic Brewing on the edge of Portland’s Mississippi District.

“We opened the brewpub on June 27 with sellable beer,” Harris said, “but the Bend Bulletin did a beer tasting later that year and Deschutes didn’t win. Gary came to me with the article in hand and asked ‘What are you going to do so that we win next time?"

That’s an easy scene to imagine, because employees and associates mention a certain intensity; Gary Fish expects no less of them than he does of himself.

“I’ve never worked for anyone who challenged me more as a chef,” said Deschutes Corporate Chef Jeff Usinowicz. “There’s always the challenge of getting better every day, and he’s not one to casually drop a ‘good job’ unless he really means it. But he’s inspirational too – at the Aspen Wine & Food Fest when Jose Andreas stopped by to say how much he liked my food, Gary raised a glass and said simply, ‘Here’s to Chef,’ – that meant a lot.

“I have a lot of love and respect for the guy,” Usinowicz said, “because he’s a true family man and the company is part of his family.”

“We have about 470 employees now (that number will edge closer to 500 early next year) and company parties do feel like family,” said Fish. “People have met here, people have gotten married, people have raised families – and now some of those kids can come in the pub and drink, it’s a pretty fine feeling.”

But Fish had to rend that family asunder in early 2003 when he fired his brewmaster, Dr. Bill Pengelly, over a difference of direction as the brewery became ever more production-oriented. “When I let Bill Pengelly go, that sent shockwaves through an industry that protects and reveres its brewers,” said Fish.

In 2002, Deschutes added a partly automated 150-barrel Huppmann brewhouse to the existing 50 barrel production system, a signal that things had changed as the company scrambled to meet growing demand in the new century. “The business had changed from a brewpub to a manufacturing operation,” Fish said, “It was the conflict of growing the business against the desires of a group of brewers who wanted to keep a very hands-on style of brewing.”

Fish makes no bones about the restaurant guy being unequal to the challenges of rapid growth. “I didn’t realize the importance of setting common goals, and I let a group of people continue to do what they wanted, even when that wasn’t in the best interest of the company. When it became clear to me that the direction wasn’t beneficial and that we weren’t going to reach an agreement, I had to take action and correct my mistake.”

“I always thought of myself as a good restaurant manager, but I was completely out of my depth,” he continued. “I let things get to the breaking point and we lost a lot of years. The business could’ve grown bigger, sooner. But we learned some great lessons, too: fix problems one at a time; take care of your people; focus on the customer; and focus on the beer in the bottle.”

“I’m a pretty happy guy sitting here 26 years later,” he said. “Yes, there are some scars, but I’m proud of what we’ve done – and will do.”