Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Innovators Series: David Blossman of Abita Brewing Co.

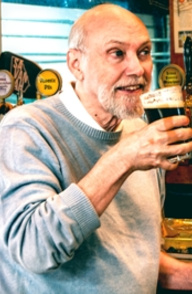

David Blossman president of Abita Brewing Co. has been on the cutting edge of craft brewing most of his life.

When he won his first medal for homebrewing, Blossman was below the legal drinking age in his home state of Louisiana. By time Blossman was eligible to drink legally, he had become an investor – albeit a one percent owner – in Abita Brewing, the first craft brewery in the Southeast and only the 13th in the U.S. at the time. Now age 46, he is closing in on two decades as president of Abita, the largest craft brewer in the Southeast and among the top 20 by volume on the Brewers Association list.

All this puts Blossman in the rare position of participating in both the second and third generations of America’s craft brewing revolution.

When homebrewers Jim Patton and Russ Cummings launched Abita Brewing in 1986, setting up a brewpub in the little town of Abita Springs about 40 miles north of New Orleans on Lake Pontchartrain, teenager Blossman began spending much of his spare time at the pub, loading trucks and doing odd jobs.

Blossman, who grew up in nearby Covington, had been fascinated by his grandfather’s stories of making strawberry wine during Prohibition. He took up brewing beer, building a five-gallon system using two buckets, a crawfish pot and burner. He drilled holes in one of the buckets to make his lauter tun.

“I became friends with Jim and Russ,” said Blossman, “I took them my beer and they’d tell me what I did wrong and what I did right.” That helped him win gold and bronze medals at the 1987 Eastern Home Brewers Alliance Competition for his helles and Oktoberfest beers. Still a teenager, he won the medals in the same year Louisiana raised its legal drinking age to 21. It was the first of several homebrewing prizes, including second and third place ribbons in the American Home Brewers Association National Competition.

When Abita’s founders carried their signature Amber lager to investment meetings in the course of their first year, they couldn’t find the money needed for growth. At David’s urging, Blossman and his five brothers soon took up the opportunity. The next-to-youngest son, Blossman thought nothing could be better than being involved in the beer business. The second generation descendents of two entrepreneurial Louisiana families, his four older brothers included a banker, stock broker, real estate appraiser and an attorney.

“I had to rely on those guys,” said Blossman. “I needed them to say, ‘Is this a good idea?’ Operating agreements, SBA loans. They had the expertise. What the hell did I know?”

Production is now 100 times the 1,500 barrels produced in Abita’s first year. Blossman says the work of founders Jim Patton and Russ Cummings ‘was phenomenal’ to get to 30,000 barrels annually after starting at the brewpub (left) in Abita Springs. The brewery moved to a location between Abita Springs and Covington in 1994.

It turns out he knew a lot about the potential of craft beer. And his belief in Patton, a Ph.D. who had taught college anthropology courses, and Cummings, an engineer, was well placed. The duo started with 1,500 barrels their first year and grew the business to 30,000 barrels within ten years. “Jim and Russ did a fantastic job,” said Blossman. “They paved the road that made my job much easier. In that environment to grow a brewery to 30,000 barrels was phenomenal. Distribution was not open to us. People were not open to higher quality full flavor ales and lagers. They had to change the perception in the market at retail and at distribution.”

Eventually, Blossman would help lead craft’s farm-to-table movement, building on Patton’s signature Purple Haze – a lager made with raspberry puree – by introducing Abita Strawberry not long after taking over as president of the brewery in 1997, using fruit from the farms in neighboring Tangipahoa Parish. “I bought a little wine press and started putting the berries in there myself,” recalled Blossman. “Everybody thought I was nuts.” The Harvest Series eventually came to include Pecan, Lemon Wheat and a Grapefruit IPA.

If there is a calling card for Abita, it is the emphasis on pairing well with the spicy New Orleans cuisine as well as pairing well with the hot and humid weather of southern Louisiana, a tradition that began under Patton with the Amber lager.

The emphasis has continued to be on lagers. “The Amber was really our beer to go well with our climate and our culture,” said Blossman. “Our cuisine, lifestyles, climate, the way we love to live. It’s really great and versatile beer. Whether it’s Creole or Cajun or Southern cooking, it goes well with all of them.”

Beers like Grapefruit IPA (oysters) and Turbodog (sausages) are more about matching up with the food popular on the Gulf Coast – and the hot weather – than following traditional style guidelines. Turbodog also makes a good reduction sauce.

Starting with untreated water pumped by the artesian well from the Southern Hills aquifer that has extremely low mineral content because it comes through fine sand and clay, Abita makes what Blossman describes as a wet beer. “Our water makes a really great beer, because it accentuates the malt characteristics, makes a very wet and refreshing beer, which happens to be what we need here in Louisiana.”

There’s another aspect to the Abita beer distinctive to New Orleans and the Louisiana Gulf. A port of call for American history with all manner of influences that produced the Creole and Cajun cultures, the bayou country is well known for feisty and spirited individualism. The Abita beer list reflects more of the local culture and less of traditional beer styles than most craft brews. Although Andygator, a helles doppelbock, won a silver medal at last year’s Great American Beer Festival in the Bock category, Abita is focused a lot more on what the locals like than traditional styles.

Turbodog, one from the original line-up, is an “old brown dog” ale that carries more oomph, hence the name. It’s been described as swampy and definitely has a strong emphasis on the malt amidst the wetness. On its own, Turbodog makes a beautiful reduction sauce for pan-cooked sausages.

At a time when IPAs are getting multiple hoppings that lead to big IBUs, the Grapefruit IPA is quite contrary; its body, taste and moderate hop bitterness are enhanced by Ruby Reds from Louisiana. “The beer has 40 IBUs without it and the grapefruit kicks it up to where it tastes like it’s got 65,” said Blossman. This luscious IPA really shines with food. With Gulf oysters, for instance, it melds with the shellfish’s liquor while highlighting the meaty taste, leaving a tangy finish.

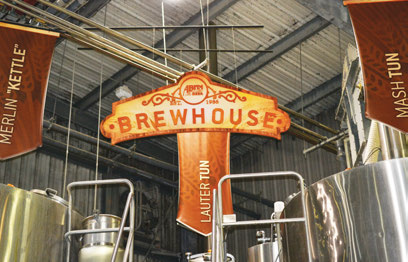

The new 200-barrel brewhouse installed by Krones that came on line this spring is part of a $12 million expansion that includes the visitor center and offices. The brewhouse features the Steinecker EquiTherm system for energy recovery.

“We’ve always danced to our own tune and do what we like doing,” said Blossman. “Frankly we make a lot of beers that we like to drink. We don’t get caught up in a craze. We do what fits us and the culture here and what the culture leads us to do.” With distribution now up to 46 states, it seems clear that like New Orleans-style cuisine, Abita’s bayou beer also travels well – in this case by a fleet of refrigerated trucks.

The energetic Blossman says he’s no longer quite as full of “piss and vinegar” as when he first began running the brewery. He talks at a quick pace without an overt accent, although a patois creeps in occasionally, such as when he adds a subtle extra syllable to “bee-er.”

Like his brothers before him, Blossman went to college at Lousiana State University in nearby Baton Rouge, where for a time he operated a 20-gallon brewing system on the second floor of a condo near the campus. He used a garden hose to bring water to the second story. As a brewery owner at Abita, albeit with a small percentage, he was careful to stay within the law. He didn’t sell the beer, rather gave it to fraternity houses, which occasionally made donations to his project.

“Jim and Russ helped me figure out how to design the system,” said Blossman. “I had plastic tubing between the different vessels. I bent my own stainless steel to make that work. I did the fermentation in a refrigerator.”

Although he occasionally ran test brews for Abita and took first place in a St. Louis homebrew competition while in college, Blossman didn’t give much thought to working at the brewery after graduation. With a degree in accounting, he went to work for Ernst & Young and soon moved to Southern Scrap New Orleans, where he rose to vice president.

After Patton became disenchanted with his role of growing the brewery instead of brewing, Blossman moved to Abita in 1996 as the vice president and became president when Patton sold his share of the company to the Blossmans a year later. At the time, Abita was brewing four year-round beers and five seasonals.

The Blossmans were majority owners, but Patton and Cummings were in charge of operations. “We got along with Jim and Russ,” said Blossman. “The way we put it, we had a third vote. We appreciated the job they were doing. They were underpaid. Jim made more as a college professor and Russ made more as an engineer than they ever made in the beer business.”

After leaving Abita, Patton went on to co-found Zea Rotisserie & Brewery, then worked as brewmaster at Key West Brewery and was helping the launch of Wynwood Brewing Company in Miami at the time of his death in 2012. In an interview with New Times of Miami, he recalled his time at Abita. “I opened a brewery because I wanted to brew. Eight years later I was sitting in an office talking to distributors and bankers and that’s not what I wanted to do.”

The timing of the change in leadership at Abita was fortuitous. There are varying viewpoints about the failures of some of the larger scale craft brewers in the mid-1990s. Whether there was a decrease in demand and sales or just a prevailing image that craft was vulnerable and a fad, the situation challenged those looking to grow.

“Russ wanted out in 1993 and then it was just Jim,” said Blossman. “I think the company got a lot more complex. Thirty thousand barrels is a lot different than 1,500. We just had some growing pains. There’s no doubt about that.

“At the time I got in, the craft business was sideways and a lot of people went out of business,” he continued. “It’s easy to feel fat, drunk and happy when business is good and you’re growing besides yourself. That growth can cover up a lot of ills. You become stronger when you don’t have that. You’ve got to rely on better production techniques, procedures and try to increase your consistency and efficiency by making a better product while at the same time managing your fiscal responsibilities.”

Blossman acknowledges that he had to grow into his leadership position and benefitted from having the right people working at Abita. In addition to his passion for brewing, Blossman’s accounting experience came in handy. “We had to improve fiscally and put ourselves in position to benefit when the growth came,” he said. “Time management, priority management are things you can learn in public accounting. Also you learn about production, shipping, risk analysis and cost analysis, which helped hone my skills.”

The risks rose with the demands of expansion. “We kept risking more and more,” said Blossman. “We endorsed all the notes. Not only did we risk the investment, I risked everything else I had. It wasn’t until seven to 10 years ago that the balance sheet of the brewery was good enough that we didn’t need to endorse the notes. And we keep putting the profits back into the business.”

Once the brewery was operating around the clock at maximum capacity six days a week, the next stage began in 2000 with the first installation in the U.S. of a Steinecker Merlin brewing kettle, which reduced time for boiling the wort and introduced energy and water savings. In 2011, a new Krones Group bottling and canning system was installed. Last year, the brewery installed one of the state’s largest commercial solar power systems.

This year, a new 200-barrel brewhouse installed by Krones has come on line. Featuring the new Steinecker EquiTherm system for energy recovery, the brewhouse covers 11,200 square feet and doubles Abita’s capacity. It’s part of a $12 million upgrade that includes an expansion of the offices and visitor’s center. The new cellaring space has room for a dozen 800-barrel tanks.

Blossman does not expect Abita to double its 2013 output of 150,000 barrels of beer and 10,000 barrels of root beer overnight. “We’re just riding the crest of the craft beer wave,” said Blossman, “and we’re going to see where it takes us.” Abita now has seven year-round beers, five seasonals, the four Harvest Series beers and three big beers, although Andygator (very quaffable despite its 8% ABV) was released in six-packs of 12-ounce bottles this spring and appears likely to join the year-round line-up.

Many thought Blossman ‘was nuts’ when he used a small wine press to create some of the first of Abita’s strawberry beers. The Abita Strawberry lager, made from fruit grown in neighboring Tangipahoa Parish, has proven very popular.

Photo Left Courtesy Abita Brewing Company. Photo Right Courtesy LouisianaNorthshore.com.

Of the new beers introduced under Blossman, which includes Abita Light, one gets the impression that the Abita Strawberry lager remains his favorite. Every family in Louisiana supposedly has a ship captain in its lineage who brought strawberries to the region for the first time after a far-off voyage. But only one family can claim to have introduced strawberry beer to the Louisiana bayou. It made its debut on draft at the Strawberry Festival, which is a big to-do around the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, in 1998. Abita now sells 100,000 cases a year and has recently re-introduced Strawberry on draft.

“Probably a lot of beer nerds and aficionados thought we were trying to sell to the lowest common denominator,” said Blossman. “People like it. It goes well down here and each year we started producing more and could not make enough. There are people who swear it’s the best beer with crawfish. Now, I would disagree personally, but I’m not going to dissuade anybody’s mind on that. People love it with crawfish. The sweetness does tend to close the palate against the spice and balance it out. You even find the beer nerds who say, ‘I hate they made it. But it’s good.’”

Starting from his grandfather’s tales of strawberry wine during Prohibition to the Purple Haze of Patton and now the unique appeal of a Strawberry lager, Blossman’s leadership of Abita continues a distinctive lineage that only seems possible down

on the bayou.