Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

The Resurgence of the American Malt House

The corporate malting industry and the American malt house is a new phenomenon in brewing and distilling.

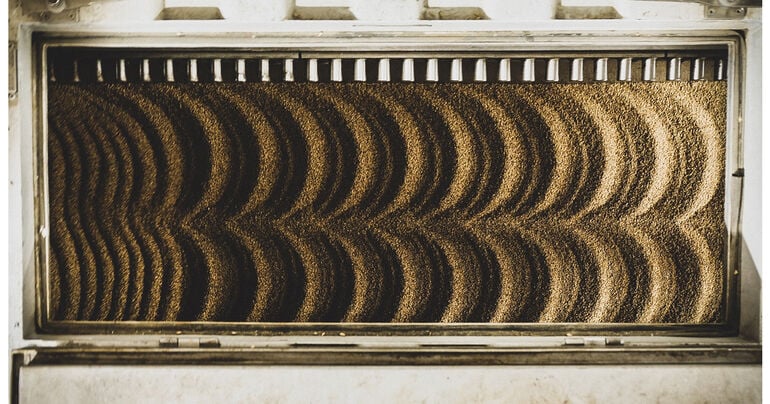

Prior to Prohibition in the 1920s, breweries and distilleries typically operated their own independent malt houses to steep, germinate and kiln-dry locally sourced grains. This process encapsulates what we mean when we talk about malting, the labor that activates the sugars that allow yeasts to make tasty, foamy, boozy brews.

Malt for brewing was a corporate affair throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. Many of the largest malt houses today exist in Europe and Canada.

The barley crop once thrived across the United States, starting with the first European immigrants on the Eastern Seaboard and moving westward for climes with steadier weather and fewer disease-bearing pests. And while the malting industry never fully went away––barley still proliferates across the Midwest and Mountain states––that practice of brewing with all-local ingredients did wither. Until recently.

In the last decade, craft malt has soared alongside the craft beer movement to take a prominent role in the brewing ecosystem. Craft malt houses and maltsters around the country are creating a diverse array of malt that imbues beers with a prominent terroir of real, local flavor.

“Throughout the first couple years, I kept waiting on the ax to fall, finding the one thing that I couldn’t overcome and realizing, oh, that’s why no one is doing this in Ohio,” says Matt Cunningham, Founder of Rustic Brew Farm in Marysville, Ohio. “But fortunately, that didn’t happen.”

Cunningham is a fourth-generation farmer who started malting with an earnest interest in proving that great grain could be grown in Ohio without the intervention of big corporations and their dehumanized, multi-million-dollar processing facilities.

As such, the system at Rustic Farms is as streamlined as possible. The three steps in the malting process (steep, germinate, kiln-dry) all happen in one of two giant steel drums. While other methods are more efficient, this way allows Cunningham to exercise his craftsman’s desire to control the environment and fine-tune the result.

In the last decade, craft malt has soared alongside the craft beer movement to take a prominent role in the brewing ecosystem.

He says, “When brewers started cold-calling me, telling me they heard about our malt from other brewers who loved it, that’s when I knew we were on to something. We have since doubled our capacity twice and are planning another expansion now.”

Cunningham and others like him around the country are pioneering what amounts to a new industry in the United States.

According to a presentation by Megan Phillips Goldenberg of New Growth Associates given at the 2020 Craft Malt Conference, the average malt house opened relatively recently, around 2014, and sees profits off an average revenue of $350,000. The timeline from first sale to profitability averages 2.5 years.

It’s not easy being a craft maltster. Corporate maltsters offer convenience with a more consistent and often cheaper product. The craft beer movement, however, has primed beer fans to expect that local ingredients can lead to unique and flavorful brews, even if that means paying a slight premium.

No small portion of craft malt’s success, however, lies in recent scientific advances that have overcome barriers to the biology of grain, and the climates that allow it to grow.

“Growing barley in the southeast, for instance, is not easy. It’s not easy in the northeast either,” says Jesse Bussard, the Executive Director of the Craft Maltsters Guild. The Guild, founded in 2013, offers education and resources for maltsters of all levels to start and grow their businesses.

“It’s challenging,” says Bussard, “but there’s research going on at universities and USDA labs across the country that are working to adapt barley to grow easier in climates and localities that, previously, it just couldn’t thrive in. And I don’t think that would be happening if it weren’t for craft malt.”

Just like every climate can’t grow barley, not all barley makes for a good malt. Whether growing their own barley or buying grains from a nearby farmer, maltsters get possible malting grains lab-tested to ensure it has low protein, good germination capacity and is disease-free. Of course, that’s only after the grains pass a physical examination concerned with kernel size, uniformity and damage.

Just like every climate can’t grow barley, not all barley makes for a good malt. As such, maltsters get possible malting grains lab-tested to ensure it has low protein, good germination capacity and is disease-free.

The science that Bussard highlights has helped craft malt industries proliferate in states that, previously, have proved very difficult for growing grain. Late last year, for instance, Cornell University announced success with Excelsior Gold, a barley designed to prosper across New York state. Excelsior Gold is a boon to the New York beer scene, providing a major step forward in how many brewers can utilize the state’s Farm Brewer’s License, which is currently only open to brewers that source at least 60-percent of their ingredients from within New York.

“Our primary variety for malting is called Butta 12. It’s new, from the University of California-Davis plant breeding program and was develop specifically to grow well in the Sacramento Valley,” says Dave McLean, co-founder at Admiral Maltings in Alameda, California.

Butta 12 is the grain that goes into some of Admiral’s most widely known and award-winning malts, like Gallagher's Best, Feldblume and Admiral Pils. It took the team at Davis twenty years to perfect Butta 12.

McLean says, “There are a lot of variables with any grain, old or new, based on terroir, farming practices and malting practices. A good maltster should be able to work with a specific variety to coax out the brewing or distilling characteristics they are looking for as long as the malt meets certain basic specs.”

Tom Hutchison, owner of Gold Rush Malt in Baker City, Oregon, epitomizes this sense of McLean’s ‘good maltster.’ He’s a one-man operation. He sources the grain, he malts it, and he even delivers it by forklift to buyers that live or work close enough to his malt house.

Gold Rush Malt made a huge impact on the craft malt landscape this year by sweeping every category in the 2021 Malt Cup––a feat no other maltster has accomplished.

The Cup awards bronze, silver and gold medals in two rotating varietal categories and then offers an additional award for best in show. This year’s varietals were Pilsen and Pale Malts, with Admiral Maltings taking bronze in Pilsen.

“You never know till you have tried a grain how well it will malt,” says Hutchison. “There is so much variety in climates that are reflected in the malt a particular grain will make. I seem to have stumbled on the right combination of variety and local climate. But I always say, each batch is a challenge and will behave differently. When it was time to send in the two submissions, I pulled a bag each of Gold Rush Pilsner and Pale off the pallets in inventory, removed the required amount for the contest and sent them in. There was nothing special about these batches, just normal everyday production.”

Craft can mean so many things. It’s a noun, a verb and an adjective. It’s a thing we work on, the way we work on it, and the reason we take to the task at all. Craft malt allows maltsters to put their mark on brewing in the most fundamental way.

Comments