Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Style Studies (Issue 18)

Once in a while, brewers come along who knows how to hit taste buds in a way that inspires deep appreciation and loyalty among beer drinkers and imitation by other brewers.

In this issue, Owen discusses how the approach to weissbier by Georg Schneider led to its great popularity and eventually to the complex and more modern Dunkels Weissbier, a style perhaps underappreciated by Americans.

In a familiar story that warrants some expert detail, the tale of Ken Grossman and his creation of the American Pale Ale comes to life in a technical discussion by Owen that sheds light on this beer’s ability to start a 20th Century aroma and taste bud revolution.

Surely there will be more discoveries in the future that change the consumption habits of beer drinkers around the world. But until the next moment of gonzo creativity arrives, we’re left to celebrate those discoveries we enjoy in the present.

Cheers!

Dunkel Weissbier

Modern craft beer enthusiasts who focus on extreme beers and the latest trends may dismiss classic German-style wheat beers, known as weissbier or weizen, as boring and passé, but one visit to a picturesque Munich biergarten in the springtime to sip a cloudy, spicy, exquisite weissbier from a tall, traditional wheat beer glass will put an end to such iniquitous thoughts.

German wheat beers employ ancient strains of top-fermenting ale yeasts that work best at temperatures around 65 to 72 degrees Fahrenheit. These microbes produce spicy, clove, vanilla, and nutmeg flavor and aroma nuances that were probably found in many ales in the Bavarian region in the middle ages. Until the mid-1800s, German wheat beers were brewed in limited quantities by monks and royal nobility and did not make up a substantial quantity of the daily beer intake of the region.

The current popularity of Bavarian wheat beers can be traced back to Georg Schneider, who opened a Munich weissbier brewery in the 1850s, then expanded production to a facility in nearby Kelheim in 1872. Surrounded by the rural Hallertau hop growing region, the Kelheim brewery survived the bombs of World War II to supply Schneider Weisse to a new generation of thirsty post-war citizens. The fame of the somewhat dark and "old school" weissbier of Schneider led many Bavarian breweries to start production of weissbiers with more golden hues during the last half of the 20th Century.

Once weissbiers solidified their place in Bavarian beer culture, brewers began to experiment once again with wheat beer recipes made with darker malts as in the early days of weissbiers. These Dunkel Weissbiers contained all the refreshing complexity of golden weissbiers but offered more of a brown color along with a multi-faceted, rich malt profile of toasted bread crust and caramel.

Malted wheat usually makes up 50 to 70 percent of the grain bill of a typical Dunkel Weissbier, with Munich, Vienna, pilsner and dark wheat making up what's left. Many think of the rich complexity of a Dunkel Weissbier as providing the refreshing fermentation character of a weissbier along with the dark malt complexity of a Munich dunkel lager. Weissbier "hefe" versions are unfiltered, with yeast sediment in the bottle that is often stirred up and poured with the beer.

A Dunkel Weissbier throws a tall, fluffy head and wafts light phenolic aromas of clove and fruity esters reminiscent of banana. Bubblegum notes should be restrained, along with any traces of spicy or floral hop fragrance and flavor. Clove-like fermentation compounds, bready wheat character and caramel-like malt complexity should be focal points of this style – all backed by a medium-light mouthfeel and spritzy effervescence.

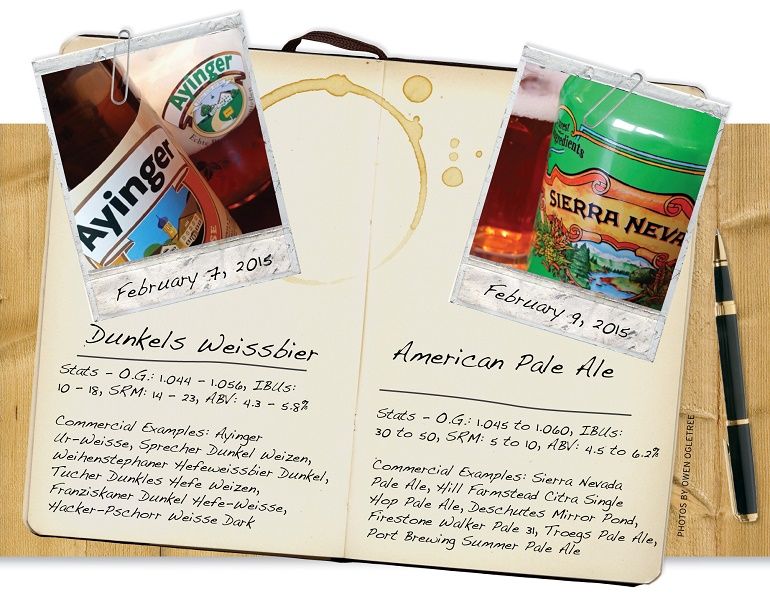

Dunkels Weissbier

Stats – O.G.: 1.044 - 1.056, IBUs: 10 – 18, SRM: 14 – 23, ABV: 4.3 - 5.8%

Commercial Examples: Ayinger Ur-Weisse, Sprecher Dunkel Weizen, Weihenstephaner Hefeweissbier Dunkel, Tucher Dunkles Hefe Weizen, Franziskaner Dunkel Hefe-Weisse, Hacker-Pschorr Weisse Dark