Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Talking Beer in 2017 with Fred Bueltmann of New Holland

New Holland's Fred Bueltmann embodies the best of the craft movement – preaching an ethos of values-driven business, collaboration over competition and a deep-rooted passion for sensory experience. We spoke with Fred to get an idea of how the game has changed for breweries navigating the Heraclitean marketplace, how craft ideology dictates decision-making and how his company has kept itself a step ahead of the curve.

A Philosophy of Quality

For Bueltmann and New Holland Brewing Co., the craft consumer's experience is the ultimate goal – making it comforting and rewarding with really thoughtful, high-quality food and drink all the way around. This mindset extends not just to beer, but food, liquor and everything in between, and is on full display at their destination brewpub and restaurant The Knickerbocker, which opened in Grand Rapids late in 2016.

For Bueltmann and New Holland Brewing Co., the craft consumer's experience is the ultimate goal – making it comforting and rewarding with really thoughtful, high-quality food and drink all the way around. This mindset extends not just to beer, but food, liquor and everything in between, and is on full display at their destination brewpub and restaurant The Knickerbocker, which opened in Grand Rapids late in 2016.

Bueltmann, also known as The Beervangelist, is a champion of craft mentality, where collaboration and friendly competition reign supreme.

"We've always felt Grand Rapids was a home market," said Bueltmann. Grand Rapids is about 30 minutes east of Holland, Michigan, where the company was founded.

"We'd been looking for a space where we could invite our customers in Grand Rapids for the past 10 years. We wanted to hold it to a high standard, and we knew when the time came that [the facility] needed to be both remarkable and an extension beyond our current organizations, because as a craft producer we should be contributing to the scene and community, providing fresh choices and elevating the game somehow."

The Knickerbocker is indeed a big step for New Holland, and a way to plant a flag in a competitive industry and showcase how craft sensibilities go way beyond beer. The facility also serves artisan spirits, handcrafted cocktails, wine and cider with a "rustic, seasonal menu showcasing local and regional agriculture, old world techniques with a fresh perspective; including nose-to-tail butchery, heirloom produce and scratch cooking over fire," as New Holland describes it. It also added about 150 jobs to the area.

Growing With Purpose

"So this particular project came together where we part of a neighborhood revitalization and we were extending what we learned," said Bueltmann. "That was a reason to open – rather than to just compete with other accounts. We want to make sure we're bringing people to the area, developing better drinkers, educating people to what's out there, getting people more confident with more adventurous choices, raising their value proposition – typically after consumers have a positive craft brewery experience, they're a little more confident in paying more for a better experience. If we can do that, we make it better for everybody, including the restaurants and bars that serve our products up and down the street."

Branching Out Naturally

"A brewery is well positioned to be a good distiller. You've got the technique, expertise, equipment to really make a fermented product free of harsh compounds or flavor defects, and we have resources a traditional distiller wouldn't have -- we're set up to lauter, separate our liquid from our grains, we have temperature-controlled fermentation. And we can share those resources.

We have separate brewing and distilling teams, but they collaborate. Both sides have learned a lot, and we as a company have learned a lot being in a marketplace other than beer, and seeing the shift in how the customer values what they buy."

With the amount of competition these days, do breweries have to branch out to stay afloat?

"Engaging in many pursuits isn't something I'd necessarily recommend to a startup brewery. I would encourage people to figure out what they plan to do really well and be exceptional at it, and really focus on that. As the company grows you can add to what you're exceptional at, but if you try and do them all that's a big task.

But that could be qualified with – 'Who's the startup?' If you have the expertise, you can modify that model to fit your organization, but I would encourage people to figure what they can really deliver that's exceptional, because we're in a day and age that your market valuation is instant, so the day that you open there's gonna be people drinking your beer and eating your food and writing about it. There's no warmup period. So, I would think about – 'what's special about what we make, and are we ready to deliver it?'

I don't think there's one philosophy of growth that's overriding. But if you look at what craft has done for the marketplace, the most important thing we've done is increase the choices the customer has available to them. More styles and interpretations, that's a form of growth that is more cultural, then there's growth of a segment – are more people drinking craft beer? I think we've all contributed to that. Then you have company growth, and everybody has their own version of it, and it depends on a lot of things – brand strength, capitalization and expansion, Often there's a big spike in the company's history when an expansion lines up, but we've always been students and proponents of managed growth – growing profitably and with stability so that we can be a strong company that's always delivering the quality experience that we stake our name to and acts as a basis for more growth."

Is that typical of craft?

There's several models. The market is getting intense with the volume of producers out there. For decades growth was more of a production riddle. The automatic growth is going away. Companies need to grow to be healthy, and we're seeing that it's going to take a little more strategy as far as where that's coming from. We always balance our growth with making sure it doesn't affect how we do things.

How do you stay true to your roots?

We do a lot of work on mission, vision and values, and teaching that throughout our company – focusing on what really defines New Holland. Identifying why you're here and what the hallmarks of your brand are make it easier to uphold, but also know when something is pulling you away from your values, so you can identify it and make good decisions. Measuring your decisions against a well thought-out, cohesive mission is going to help you stay true to who you are. Customers don't always see that work behind the scenes, the nuts and bolts, but they know when a brand feels like it hasn't left its core identity. Remembering to do work on company culture and educate your teams brings you a little more sure footing.

Friendly Competition

Over the years we've increased the amount of data we look at and how we integrate it into our planning. I've always described some of the craft-on-craft competition as sibling rivalry where you want to compete and win, but you're not looking to hurt the other participant. You want people to drink better, and we've all fought to make a change and improve the marketplace so when there's somebody else doing good work you're not rooting for them to fail because we've all got the same cause.

We're coming up on 20 years, a heritage brand. You can't allow your values to become a passive voice. You still have to be a professional that can protect your brand in the marketplace, stick up for yourself and ask for the shelf/tap space and promotion so the consumer can know where to find you and what you provide. We still have to compete and act assertively to market our brand so we're not overlooked.

On Branding

On Branding

"There's a couple of models of branding beer styles. We did what I would consider to be 'iconic branding' – a brand icon, mark, character and fanciful name. So instead of selling New Holland IPA, we're selling Mad Hatter IPA. That's a choice we've stuck with, and it helps engage visual memory and those beers can become characters in people's stories. The other model, of saying 'brewery plus style equals brand' is a perfectly valid approach, but it's going to be different. We've always looked at [our branding] as a collective artistic process and we've enjoyed the opportunity to create images and icons, and that helps people remember us."

"As an older brewery with a wide portfolio, it's more appropriate to bring a smaller list of beers that offer something special to the market, rather than trying to bring your whole book."

"Creating intellectual property and coming up with a name someone hasn't used yet, that's never been more challenging. When you have to create a new icon for every new brand, your work is cut out for you. We've always believed one of our assets is our ability to create. We believe in our team and their ability to create."

What do you think of specialized brewers, who only brew a certain style?

"It helps develop a reputation, and it's an opportunity for new brewers. Current breweries don't have to satisfy everything the consumer will ever drink. You'll see a lot of 20+ year old breweries with a pretty broad portfolio, because they were the game in town and needed to provide all the choices. The more specialized breweries are typically younger."

Ruling the Roost

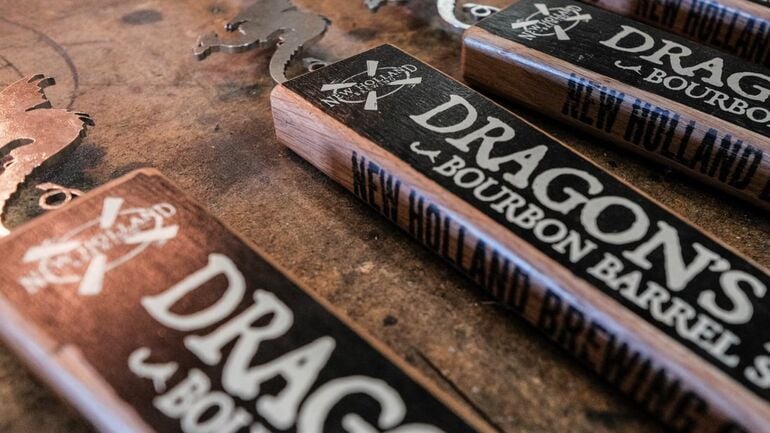

"We're really excited to be bringing Dragon's Milk to more places – what we're calling the "unlimited release." We've put a lot of work in over the last 15+ years -- figuring out how to make more of it more often. Barrel-aged beers have complications in terms of consistency and shelf stability. We've been amazed to see that brand grow the way it has. I think it's special to have a beer that's so often a limited release available all the time. What seemed outlandish at one point, an 11% ABV $15.99 four-pack is now our top seller. That's a credit to the craft drinker and our team."

Distribution Strategy

"As an older brewery with a wide portfolio, it's more appropriate to bring a smaller list of beers that offer something special to the market, rather than trying to bring your whole book. With beer tourism and travel on the rise, it's important to 'edit' ourselves, and to have people know that if they come to the Midwest, they'll get a deeper lineup... I think drinkers engage with fluctuating, diverse choices – seeing the landscape change, so we're making thoughtful choices about what we offer, and where, and how that can be invitation and a sense of pride. If you're coming to our pubs, you'll have a deeper list of choices than you'd see elsewhere."

Looking Ahead

"For younger breweries, you have to be strategic and efficient with where you bring products, why you're bringing them and how they're going to succeed. It's the greatest time in the world to drink, with so many choices, but that's not without challenge in terms of producers. We have to partner to create clarity, and make sure the beer is fresh and moving off the shelf. We have to have good collaborators and make sure that we're being thoughtful to make sure this shift is a positive one, and not negative.

When we step into this arena, we want consumers to be exposed to an elevated experience. We have to be stewards of quality, making sure the products we put out are exceptional and composed, not rushed. We all have to continue to invest in our ability to deliver quality products.

Whether it's to beer producers or readers, as we're in this interesting but complex period of growth, when the growth levels off, people will bring up the 'bubble bursting.' Things slowing to some degree as an industry can be a plateau, but I like to think of it as a stairstep, that a little leveling off can sometimes calm and settle before you go off to the next step. I just encourage people to not take any news of slowing and closing as 'the sky is falling.' Take that with a grain of salt.

[Craft is] still less than 20 percent of the market. There's a whole lot of people in that 80 - 85 percent that can still come in. There's really no end to our potential as craft and individual brewers. We want to make sure we're inviting people in, welcoming them and providing a remarkable experience.

We have to run our business professionally, smartly, and provide expertise and leadership to our industry collaborators. And I think that's different from pounding our fists on the table and thinking that end is near. The challenges are real, but we must rise to the occasion."