Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

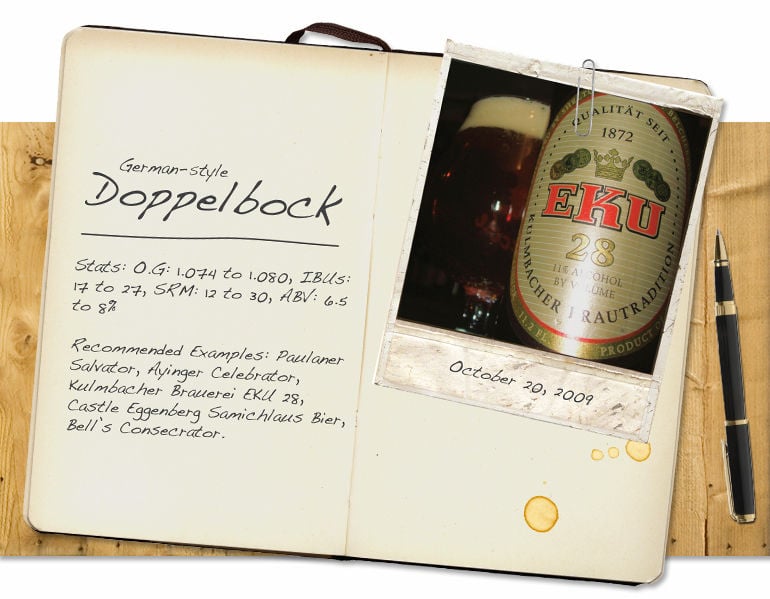

What is Doppelbock?

For all its arguable foibles and missteps throughout recorded history, the Church has always been rather adept at brewing beer. Thank God for that. The modern doppelbock style, derived from the earlier bockbiers of Bavaria and made famous by the brewing monks of St. Francis of Paula in Berlin during the 17th century, is an excellent example of this fact.

Originally brewed as a more substantial beer to sustain the monks during lengthy fasts, particularly the Lenten season, the strong beer that would later come to be known as doppelbock was dubbed “liquid bread” for its satiating qualities. Most likely the historical beer the Paulaner monks imbibed was somewhat sweeter, being less attenuated, and thus lower in alcohol than many contemporary examples. But today’s doppelbock is certainly an antecedent of the original ecclesiastical brew inspired by the Bavarian tradition, as well as by God, as it was given the name “Salvator.”

Both pale (helles) and darker versions exist today, but the darker examples are far more common. The former examples utilize larger amounts of pale malts, like Pils or Vienna varieties, to impart lighter color and more subtle flavors, and they are often somewhat drier and hoppier. Pivovar Náchod Primator is a well-known example of a helles-style doppelbock. The darker examples rely on specialty malts like Munich and Carafa to impart the famous color and rich maltiness commonly attributed to the style. Paulaner Salvator is the most famous example of this traditional doppelbockbier.

The “-ator” suffix is a typical naming convention for doppelbock beers, both as a nod to the Paulaner beer and because patent laws finally prevented other brewers from using the “Salvator” name for their similar beers. The image of a goat is also closely associated with the bock style in general. There is not monolithic agreement, however, as to the origin of the “bock” name itself. The goat imagery makes sense in that the word bock translates to goat in German, but why a goat? Another notion is that bock is a corruption of Einbeck, one of the earliest brewing cities in Lower Saxony.

As for the beer itself, the doppelbock style can range in color from a rich gold to dark ruddy brown. Expect very good clarity as a result of the lagering process and a thick, creamy head of foam that retains well. The head can vary between white and medium caramel color, depending on the darkness of the beer.

On the nose, expect pronounced malty notes right up front, and some bready, toasty character is not uncommon, especially in the darker examples. Some suggestions of caramel and chocolate may also be found, and alcohol may be slightly discernable in stronger examples.

Doppelbocks are malt-dominant beers and the palate is summed up in rich maltiness with some contributing toasted and caramel aspects not unlike that of molasses. The stronger and the darker the beer, the more pronounced the toasted character tends to be, though the roasted, burnt characteristics, like those found in stouts, should not be present here. Flavors should be clean, smooth and slightly sweet with very little hop bitterness. The finish is medium-full and very smooth, with some alcohol warmth in the finish.

Doppelbock beers are rich in both history and flavor. These beers hold up well paired with strong and savory dished like venison, cheeses such as brie or havarti, or as a compliment to a rich crème brûlée or tiramisu.

Look here for Doppelbock reviews by our panel of judges.