Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

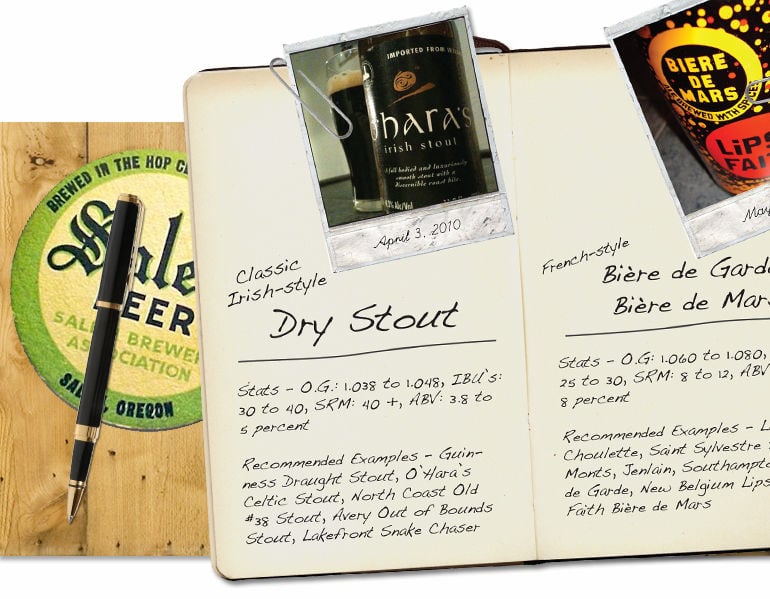

What is Irish Stout?

Thankfully, not everyone who joins in the annual revelry on March 17th drinks the obligatory and ubiquitous green lager beers. Instead, many opt for what they consider to be a more traditional style – the Irish stout. Though not all dry stouts are from Ireland and not all Irish stouts are necessarily dry, this particular easy-drinker has become synonymous with St. Patrick’s Day celebrations and all things Irish.

Guinness typifies the smooth, creamy texture and roasted malt flavors that the style is known for, though its earliest versions – even the earliest versions of Guinness itself – were quite different from the relatively light and clean stout you’ll find being poured today. The robust malt profile and yeasty complexity found in early bottle-conditioned Guinness has been replaced with a far more meager malt body, a simplified flavor profile and the use of a nitrogen draught system. Nitrogen infuses the beer with tiny, dense bubbles that lend a perception of smoothness and creaminess to the beer when it is served on draught or out of a can equipped with a floating nitro-widget. Many beer purists, however, tend to frown on the use of nitrogen in beer, as this technique, it is argued, tends to diminish the full perception of malt flavor and detract from the beer’s inherent qualities.

Dry stouts – and indeed all stout styles – can be traced to the “stout porters” that were popular among London’s working class during the 18th century. Originally brewed as stronger “stout” versions of the porter, stouts maintained their popularity in countries like Ireland while paler beers were becoming accepted in their English birthplace. The beer that would come to be known as the Irish dry stout, then, developed its identity around an emphasis on the use of unmalted roasted barley, bittering hops over those that emphasize flavor or aroma, and the common use of a small percentage of sour malt to add complexity and character to the finished beer. While this technique didn’t result in the level of sourness commonly associated with, say, the German Berliner Weisse style or the spontaneously fermented Belgian sour beers, the archetypal dry stout possessed a character that was far more complex and flavorful than the extant versions of the style widely available today.

Though the most popular and prevalent examples of dry stout in the United States belong to the Guinness, Murphy’s and Beamish brands, there are both Irish brewers and numerous American craft brewers trying their hands at recreating an approximation of the dry stouts of old. These flavorful stouts exhibit a coffee-like nose accented with hints of chocolate and a touch of caramel. Their color is often the deepest brown to black, and they produce a billowy tan head of foam despite the lack of nitrogen infusion. Bottle-conditioned versions are often near opaque in color and include a subtle hint of pungent yeast in the nose. The flavor profile is a unity of roasted malts, baker’s chocolate and caramel, with a decided emphasis on the first two elements. Some versions even include the subtle sourness produced by a sour mash addition or the use of lactic acid. Hops are used in the style strictly to emphasize bitterness over hop flavor or aroma. Generally well-attenuated, the dry stout’s impression in the mouth is what the name suggests – dry – with a surprisingly light body, high bitterness levels, a slight astringency and a surprisingly clean finish, with lingering notes of coffee and chocolate. Dry stouts are meant to be perceived as smooth, never harsh or overly acrid.

So whether you’re a dry stout drinker only while you’re sporting a shamrock or you enjoy this smooth, drinkable beer all year long, be sure to heighten your stout-drinking experience with an appropriate food accompaniment, like the classic pairing of raw oysters, lobster, sharp cheddar or a hearty beef or lamb stew.