Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Michael Jackson: The King of Beer Writers

On the morning of August 30th nearly three and a half years ago, I woke up in my hotel room in Yakima, Wash., a little hungover, having spent the previous two days attending Hop School. With a pounding head making it impossible to sleep, I gave up trying and opened my laptop to check my e-mail. After deleting the usual spam, I saw an unexpected note from a friend and colleague. It was short and to the point. The subject line read: “ Michael Jackson has died.” I glanced at the clock. It was 5:11 a.m.

I sat there in the dark in stunned silence. I’m just barely old enough to recall my parents telling me J.F.K. was shot, but I know exactly where I was when I heard the news that John Lennon had been killed. This was different. Michael Jackson (aka The Beer Hunter) was not just a celebrity or a personal hero, he was also someone I actually knew and was lucky enough to call both colleague and friend. Like many beer connoisseurs, he had been one of the catalysts for my love of good beer. Like many beer writers, his work inspired me to do what I do today.

I was certainly not alone in those feelings, as evidenced by the torrent of grief, celebration and remembrance that followed in the weeks after Jackson’s untimely death at 65. The force of the emotional outpouring was a testament to just how much he meant to an entire industry and generation of brewers.

But I Digress…

For Jackson, his love of beer was boundless, but it was never only about the beer. It was equally about the people and the stories behind the beer. He was a consummate storyteller. In public speaking, he was prone to tangents; in fact, his many digressions were the norm, his signature style. A thought would occur to him in the middle of a speech, and off he’d veer in a different direction, listeners happily following him down the rabbit hole. He might wander off again, remembering a related anecdote before circling back to the main thread of his story. In the midst of such chaos, he may have seemed rambling to the uninitiated, but he always tied up loose ends and made his ultimate point. It’s what made his stories lively, engaging and very personal. Jackson made the beer and the breweries come alive. He made people want to drink beer. His enthusiasm was infectious.

Jackson’s own childhood story was by contrast almost unremarkable. He was born 69 years ago this March in England in the small market town of Wetherby – part of the city of Leeds – in the northeast corner of West Yorkshire, but was raised in the nearby working-class town of Huddersfield. His grandfather, Chaim Jakowitz, moved the family to Yorkshire from Kaunas, Lithuania. Jackson’s father Isaac, by trade a truck driver, anglicized the family’s Jewish name and married Margaret, a gentile woman he met in a local dance hall while serving in the British Army. Michael had a sister, Heather, and briefly a twin brother who died not long after they were born.

It was Jackson’s mother, who worked as a baker, that instilled in him a love of words. He dropped out of King James’s School in nearby Almondbury at age 16 to contribute financially to the family and became a cub reporter at The Huddersfield Examiner. After learning the newspaper craft, he worked for a time in Edinburgh – where he developed his love of whisky – before eventually finding work in London.

Jackson wrote for The Daily Herald, at least until it folded in 1964, after which he took over a journal covering the world of advertising and marketing called Campaign.

He married Maggie O’Connor in 1966, but she passed away in 1980 after they had spent nearly 14 years together.

Craft Beer Before Craft Beer Was Cool

It was being a reporter that provided Jackson with opportunities to drink different beers as he traveled the country for work, and he wrote increasingly about beer as his interest grew. He expanded his horizons and began writing for such diverse outlets as The New Statesman and the adult magazine, Oui. Jackson also branched out into television, working as a program editor on “The David Frost Show” and producing documentary films.

An extended job as a journalist living in the Netherlands in 1969 convinced Jackson that bland European pilsner-style beers were not for him. One weekend he took a trip south to cover a local carnival near the border of Belgium. It was there that he first tasted a Trappist beer. He was so smitten with the complexity of the beer that the following day he crossed the border – his Rubicon – and began exploring Belgium’s beers and culture. During subsequent trips to Germany and the Czech Republic he made similar revelations, which convinced him of the diversity of beer around the world.

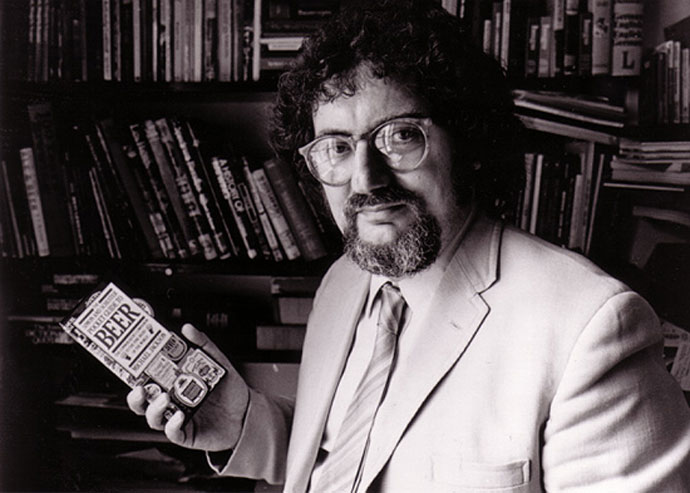

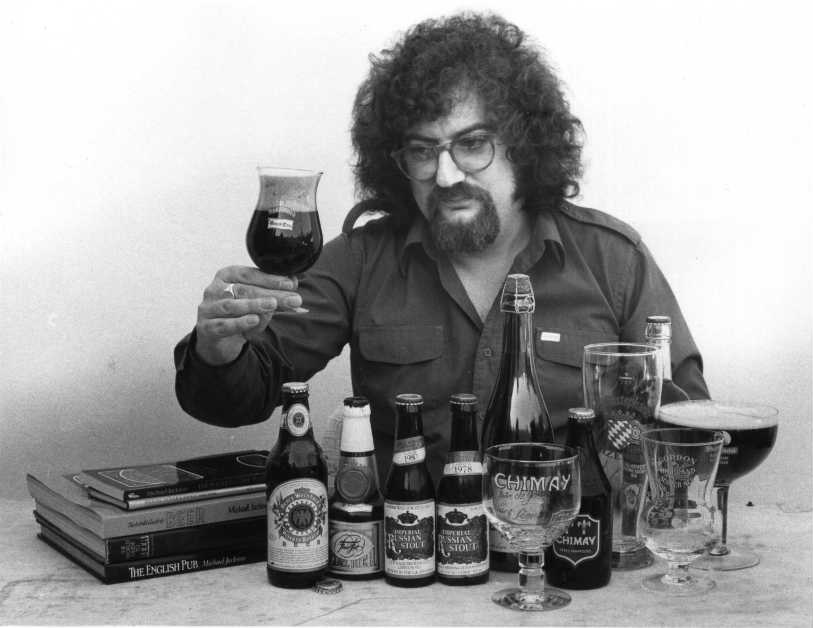

Photo Courtesy Celebrator.com

Putting Pint to Paper

In 1976, an opportunity presented itself that was too good to pass up. A writer contracted to produce a book about English pubs for Jackson Morley Publishing reneged on the deal, and Jackson stepped in to write it. The assignment was to examine pub culture and, as the subtitle suggested, its “unique social phenomenon.” Writing about the beer itself was not to be part of it, but beer spilled into the book’s pages and the die was cast.

A year later Jackson published the “World Guide to Beer.” It was groundbreaking in the way it approached beer and immediately made him famous, especially in beer circles. Jackson imported and adapted descriptive language from the world of wine to talk about beer. The book divided the world not only geographically, but also by the types of beer each place produced. He recognized that different historical brewing traditions created varied beers that were unique and reflected the culture of the people who brewed them.

“The World Guide to Beer” was, compared to what came before it, “the difference [between] a gueuze and a Miller Lite,” according to Charles Finkel, the founder of both the beer import company Merchant du Vin and Seattle’s Pike Brewery. In particular, most defined the world of beer in very narrow terms, as Finkel notes:

“In ‘The Taster’s Guide to Beer Brews and Breweries of the World’ by Michael A. Weiner, 1977, Weiner gave three paragraphs to Belgium and mentions only one beer, a lager. Bob Abel’s 1976 ‘The Book of Beer’ at least mentions lambic in one paragraph, and mentions five lager brands.”

“It was powerfully encouraging and inspirational to have Michael sit and taste your beers,” says Matt Brynildson of Firestone Walker. “His ability to process and articulate what he experienced was truly unique.”

Drinking with Styles

Perhaps Jackson’s biggest contribution to beer was his invention of the taxonomy of beer styles. As British beer historian Martyn Cornell explains it:

“He invented the expression ‘beer style,’ which was found nowhere before ‘The World Guide to Beer’ appeared, forcing brewers and drinkers to think about the drink in a way they never had before when they talked merely of ‘varieties’ or ‘types’ of beer. He introduced drinkers to beers they would probably never have heard of without his work, and he encouraged brewers, directly or indirectly, both to revive old styles and to push the envelope until, sometimes, it tore in their efforts to come up with new styles.”

It’s hard to imagine craft beer today without his notions of beer style. It not only allowed brewers to imitate and perfect different kinds of beer but also revealed opportunities to experiment and innovate, producing new types of beer in the process. And throughout his life, such creativity was something Jackson encouraged and supported. Fellow beer writer Stan Hieronymus recalls just how forward thinking Jackson was, even in those early days:

“Beer was his turf. He was the expert. Status quo would have served him well, but he embraced brewers who were willing to experiment. Not everybody was as willing to accept then that the next generations may have different tastes.”

Coming to America

As famous a beer expert as Jackson had become in his native England, it was in America where he arguably had the biggest impact and influence. He began visiting microbreweries all around the country in the early 1980s, no matter how remote their location. Perhaps more importantly, he was generous with both his time and his encouraging support. He rarely, if ever, gave a negative review that wasn’t constructive. He applauded the effort and delved into the stories surrounding the new breweries and the beer they were making.

Virtually every pioneering craft brewer has a story about being visited by Jackson, and many insist they were even life changing.

In 1981, the Brewers Association’s founder, Charlie Papazian, was attending the Great British Beer Festival in London, where he discussed with Jackson whether he thought such a festival might be successfully translated to the U.S. The following year, the Great American Beer Festival was born and is today the largest festival of its kind anywhere.

Even before Jim Koch launched his Boston Beer Company, Jackson was a guest at Koch’s home during a 1983 visit to the States. While downing a dozen cups of coffee at breakfast, he proceeded to critique in great detail all of the beers (and whiskey) that he and Koch had shared the previous evening. Shortly thereafter they began tasting Koch’s homebrew. Koch remembers Jackson treating beer with a reverence that at the time was nothing short of inspirational:

“What I learned from Michael was to take a beer seriously in all its aspects. Its history, its creation, its geography, its ingredients and its role in human civilization and modern culture. As part of that lesson, I learned to talk about beer thoughtfully and with deliberation and respect.”

Carol Stoudt had a similar experience when Jackson visited her brewery, Stoudt Brewing, in rural Pennsylvania in 1987. “At that time, we made three kinds of German-style lagers, but he encouraged us to experiment with lesser-known styles.” As a result, Stoudt remembers, “We went back to Germany to learn and understand about these different beers. On a subsequent visit, he tried our rauchbier – which was not selling well – and loved it. He told us not to worry, that people would come to like it.

“Michael just had a passion for all beer, respected the brewer, and I never heard him talk negatively about any beer,” says Stoudt. “Instead he’d say, like a pat on the back, ‘it’s going to happen.’”

That’s a story endlessly repeated. Papazian likens Jackson’s early support to parenting, saying he “embraced the early days of the American brewing renaissance as though it were a child. In the early 1980s he recognized the embryonic American attitude, which was to foster the creativity, innovation, fun, reverence, tradition and respect for beer.”

Later generations of brewers viewed Jackson with awe and even a little fear or nervousness. As Firestone Walker’s brewmaster, Matt Brynildson, recalls:

“It could be rather nerve-racking for a young brewer to sit and drink one of your own beers with him, but he had a beautiful knack for focusing on the positive attributes of whatever he was tasting and not over-analyze it, as many brewers tend to do. It was powerfully encouraging and inspirational to have Michael sit and taste your beers. ‘Mind-opening’ better describes the experience. His ability to process and articulate what he experienced was truly unique.”

Photo Courtesy Running Press

But I Digress… Again

In the mid-’80s, Jackson held what is considered to be the first beer dinner, technically a lunch, in which each course was prepared and paired with a different Belgian beer. Four Belgian chefs cooked for the event, which was held at the Pierre Hotel in New York City.

Jackson had a deep love of good food, instilled at an early age by his family’s rich Jewish and Eastern European heritage, and throughout his life he championed its relationship to beer. For well over a decade, he hosted the now legendary “Book and the Cook” beer dinners, held annually at the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. Monk’s Cafe, also in Philadelphia, likewise hosted Michael Jackson beer dinners, and the idea slowly caught on as dinners, with and without Jackson’s involvement, began to take root around the country.

Around 1987 he began turning his attention to single malt whiskies, the result of which was the “Malt Whisky Companion,” which quickly became the best-selling book ever written on the subject.

The following year, Jackson published an updated edition of his most famous work, this time with a slightly different title, “The New World Guide to Beer.”

In 1990, his six-episode documentary series on beer produced by Britain’s Channel 4, “The Beer Hunter,” aired in the U.S. on PBS and was an immediate hit. It reached a whole new audience, and Jackson became almost a cult figure in the States.

At that same time, the proliferation of microbreweries and brewpubs exploded, and Jackson was very much in demand. He lectured on university campuses, such as Oxford and Cornell. He also spoke at the Culinary Institute of America, the Smithsonian Institute and the National Geographic Society. Jackson was a frequent guest at much smaller venues, such as Washington, D.C.’s famous Brickskeller and many other “beer bars,” then also a new phenomenon stemming from the rising interest in beer. He became a regular columnist for several newspapers and contributed to magazines like Esquire, Playboy and Food & Wine.

A Writer’s Draft

The new popularity of beer in the late ’80s and early ’90s also brought with it a raft of new magazines focusing on beer and beer culture. These new publications needed writers and, in effect, a whole new profession was born. Many of us who write about beer professionally got our start during this time period. And it was again Michael Jackson who showed the way. As he did for brewers, he did for writers, too. He was not only generous with his time but also encouraging and supportive of our efforts. Many of us feel we would not be where we are today without Jackson. Stephen Beaumont expressed it this way:

“It is not a stretch to say that if Michael hadn’t done what he did in terms of writing about beer, I probably wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing. I taught myself about beer and how to taste largely from Michael’s books, and later received encouragement from him when the going was the toughest. To say he was an inspiration is telling only a piece of the story.”

Lew Bryson was equally effusive, saying, “Michael opened the path my life took. Nothing less.”

While there were certainly authors writing about beer before Jackson, by his example and influence he created not only enough interest and work for himself but made possible entire careers in a new specialty field that he essentially created for an entire generation – the beer writer.

Another Digression

“The Great Beers of Belgium,” a thorough look at the beers and breweries of Belgium in a way never done before, came along in 1991. It brought so much attention to that nation’s beer that the book is even credited with saving some breweries that had been on the brink of bankruptcy prior to its publication. The book ran to five editions during Jackson’s lifetime and a sixth edition was completed posthumously. In 1997, Jackson was made a member of the Belgian Confederation of Brewers for his contribution in promoting Belgian beer, an honor previously reserved exclusively for brewers.

Two years later, Jackson published the “Beer Companion,” arguably his most important book on beer. It went even further in dividing up the world’s beer styles, this time abandoning geography entirely and instead organizing them into six broad types, with more specific styles within each. In that book’s opening chapter, he neatly sums up his life’s mission:

“No one goes into a restaurant and requests ‘a plate of food, please.’ People do not simply ask for ‘a glass of wine,’ without specifying, at the very least, whether they fancy red or white, dry or sweet, perhaps sparkling or still.”

Jackson concludes this thought several paragraphs later, revealing his ultimate purpose: “Beer is by far the more extensively consumed, but less adequately honored. In a small way, I want to help put right that injustice.”

His success, it may be argued, was by no means small. Many more books followed, both on beer, whisky and even entertaining in general. In 1997, he updated the “Beer Companion,” and a year later published “Ultimate Beer.” The new millennium brought “Michael Jackson’s Great Beer Guide,” “Scotland and its Whiskies,” and, in 2005, “Whisky,” for which he won a coveted James Beard Foundation Award.

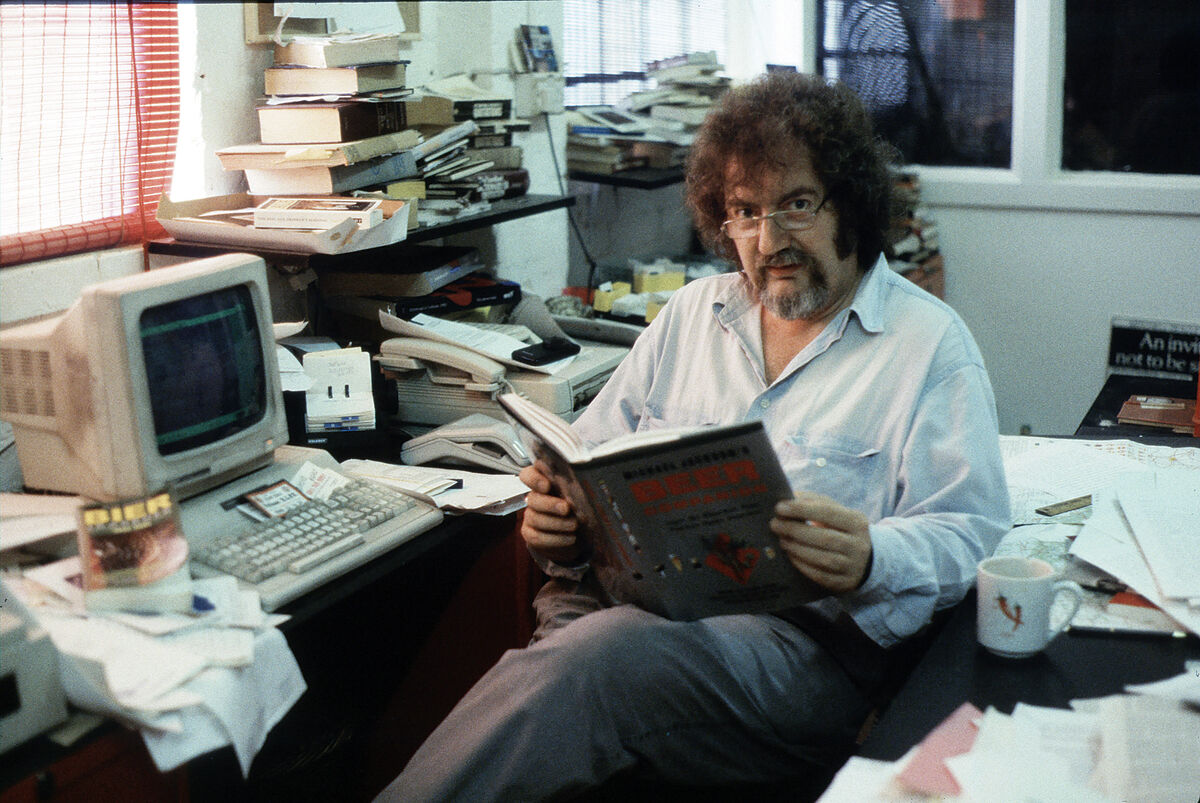

Jackson’s intelligent approach to beer, beginning with his development of a brewing taxonomy, informs practically every facet of the culture as it exists today. (Photo by Charlie Papazian)

Personal Challenges

In late 2006, Jackson finally revealed that he’d been battling Parkinson’s disease for at least a decade, and possibly longer. Although he would have preferred to keep it private, the growing rumors that he was drunk in public during his many appearances made that impossible, if for no better reason than to set the record straight. Changes to the measure and type of his medications were the cause, and when not employed effectively gave the impression of a person with slurred speech and impaired motor functions; in other words an inebriated person.

A Final Tangent … Another Side of Michael

While undoubtedly beer became Jackson’s great passion, it was not his first or only love. In addition to an obvious affection for whisky, he was also a lifelong fan of rugby league, which he apparently played successfully as a young man.

He was also a devoted lover of jazz, something I personally had in common with him. In the ’70s, I worked as a saxophone player in New York City, and it was in jazz clubs there that I was first introduced to better beer and led to Jackson’s writing. Whenever I saw Michael, I’d bring up music or the latest book I was reading. His face would usually light up and we’d talk at length. While everyone seemed to want to discuss beer with him – and he happily did so – I learned that he seemed to appreciate the opportunity to talk about other subjects.

A Lasting Legacy

Toward the end of his life, Jackson received recognition and awards for his contributions and service to both beer and whisky. He won the Andre Simon Award, the Glenfiddich Trophy, and awards from both the British and North American Guild of Beer Writers. In addition to his native U.K. and the U.S., Jackson was also honored in Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and Italy.

In trying to sum up the legacy that Jackson left both the beer community and the wider world, I keep returning to his ability to personalize whatever he was talking or writing about, and how he touched the lives of everyone he met. Since people were such an important part of his own philosophy, some of his closest friends and colleagues are perhaps best suited to sum up that legacy.

Stan Hieronymus reminds us that “we taste his legacy every time we put a beer to our lips and think about what’s in the glass.” And to Stephen Beaumont, “his legacy is the diversity of beer we enjoy today.”

For Tom Dalldorf, the publisher of Celebrator Beer News, “No other writer has had such a profound impact and influence on the beer industry – or ever will.” He “gave the pubescent American brewing industry the concepts needed to succeed and the confidence to explore, innovate and push the envelope on brewing styles and techniques.”

According to Lew Bryson, it was getting beer to be “taken seriously” that was Jackson’s legacy. “Michael became big enough, and revered enough, that he gave gravitas to beer. We owe him, and always will.” Randy Mosher, the author of “Tasting Beer,” echoes that sentiment, saying, “His greatest contribution as far as I am concerned is that he was the first writer to actually have the outrageous notion that beer could be taken seriously.” For Charles Finkel, he did this by being “a superb teacher. He taught people that beer, like wine, is a gastronomic drink of culture, taste, character, custom and history. The American craft beer industry and the influence that it is having on the whole world can be directly attributed to Michael Jackson.” To the beer writer Carolyn Smagalski, he “was, without a doubt, the Father of the Craft Brewing Renaissance in America.”

And as for brewers, Tom Peters, the owner of Monk’s Café, observed, “Michael would encourage some brewers to keep traditions alive and other brewers to really push the envelope of what is possible.” To Sam Calagione, the founder of Dogfish Head Craft Brewery, “Michael Jackson means to the beer community what Robert Johnson means to the rock community – the prototype-catalyst-evangelist – he’s the man who got people drinking outside the lines.”

After Jackson’s death, there was a tribute given in his honor at the Great American Beer Festival. A large banner was hung from the ceiling showing the familiar shot of him looking over a globe with a glass of beer in hand. It’s a fitting image, because from the floor of GABF Michael appears to be looking down from heaven, keeping a watchful eye on the craft beer industry he inspired. Every year, I take a moment to glance up at him and raise my glass to drink a silent toast.

Though gone, Michael Jackson will not be forgotten. Through his vast body of work, he will live on and will continue to inspire and influence generations of beer lovers and brewers to come.